doi: 10.62486/gen202452

REVIEW

Gentrification of tourism: a bibliometric study in the Scopus database

Gentrificación del turismo: un estudio bibliométrico en la base de datos Scopus

Chris Nathalie Aristizábal Valbuena1

![]() *

*

1Universidad del Quindío. Armenia, Colombia.

Cite as: Aristizábal Valbuena CN. Gentrification of tourism: a bibliometric study in the Scopus database. Gentrification. 2024; 2:52. https://doi.org/10.62486/gen202452

Submitted: 16-06-2023 Revised: 17-09-2023 Accepted: 05-01-2024 Published: 06-01-2024

Editor: Estela

Hernández-Runque ![]()

Corresponding Author: Chris Nathalie Aristizábal Valbuena *

ABSTRACT

The study provides a comprehensive analysis of how gentrification and tourism intertwine and affect urban environments. Using a bibliometric methodology to review publications between 2018 and 2023, the study identifies the main trends and dynamics in the literature on this topic. The results reveal a growing academic interest in the interaction between gentrification and tourism, with a geographic concentration of studies in Europe and North America, although research is also emerging in Asia and Latin America. Key words highlighted in the literature include sustainability and social impact, highlighting concerns about equity and access to tourism benefits for local residents. This bibliometric analysis offers valuable insights into the consequences of tourism gentrification and suggests the need for more inclusive policies that balance economic development and social justice in urban contexts transformed by tourism.

Keywords: Gentrification; Tourism; Sustainability; Social Impact; Urban Policies.

RESUMEN

El estudio proporciona un análisis exhaustivo sobre cómo la gentrificación y el turismo se entrelazan y afectan a los entornos urbanos. Utilizando una metodología bibliométrica para revisar publicaciones entre 2018 y 2023, el estudio identifica las principales tendencias y dinámicas en la literatura sobre este tema. Los resultados revelan un creciente interés académico en la interacción entre la gentrificación y el turismo, con una concentración geográfica de estudios en Europa y América del Norte, aunque también emergen investigaciones en Asia y América Latina. Las palabras clave destacadas en la literatura incluyen la sostenibilidad y el impacto social, subrayando preocupaciones sobre la equidad y el acceso a beneficios turísticos para residentes locales. Este análisis bibliométrico ofrece perspectivas valiosas sobre las consecuencias de la gentrificación turística y sugiere la necesidad de políticas más inclusivas que equilibren desarrollo económico y justicia social en contextos urbanos transformados por el turismo.

Palabras clave: Gentrificación; Turismo; Sostenibilidad; Impacto Social; Políticas Urbanas.

INTRODUCTION

Gentrification is an urban phenomenon predominantly observed in neighbourhood revitalization contexts. It has become intertwined with the tourism industry in recent years and has attracted the attention of academics, activists, and local governments.(1) Traditionally associated with the displacement of low-income residents and the transformation of districts into high-demand visitor centers, gentrification has emerged as a crucial field of study for urban planners and sociologists.(2,3,4) However, its relationship with tourism has yet to be explored despite the evident connections between the two processes in changing the urban and social landscape.(5,6,7)

This study used a bibliometric methodology to analyze publications in Scopus from 2018 to 2023, identifying research patterns, publication trends, and key thematic areas. Through the literature review, the article seeks to elucidate how scholars and practitioners have addressed the intersection of gentrification and tourism. In addition, it explores how tourism can act as a catalyst for different phenomena due to gentrification in different geographical contexts.(8,9,10)

It should be taken into consideration that research on tourism gentrification is essential to understand not only the economic and social consequences for the residents of the affected areas but also to plan more effectively for sustainable tourism management and development.(11,12,13) While gentrification can improve infrastructure and services, including tourism, it poses significant challenges, such as losing cultural identity and excluding residents from economic benefits.(14,15,16,17,18) This research contributes to the global discussion on balancing these effects, proposing a more inclusive and sustainable approach to urban and tourism development. The latter is one of the main needs given an adequate gentrification process.(19)

METHOD

The study used a bibliometric methodology to analyze the volume and trends of scientific literature on the interaction between gentrification and tourism. A comprehensive review of the Scopus database was conducted, selecting publications between 2018 and 2023, using the keywords “gentrification AND tourism”. This search strategy was designed to capture the widest possible range of relevant studies addressing gentrification and tourism in diverse urban and geographic contexts.(20,21,22,23)

Data selection

Articles were filtered to include only those that were directly related to the topics of gentrification and tourism. Publications that explicitly addressed both concepts were excluded. Data extracted included article title, papers by year of publication, abstract, number of citations, and keywords.

Bibliometric analysis

The analysis was performed using VOSviewer bibliometric software, which allowed a quantitative and visual analysis of the data. Key metrics were calculated, such as:

· Total publications to understand the trend of scientific production on the subject.

· Citation trends to assess the impact and influence of publications.

· Geographic distribution to identify where studies were concentrated and how gentrification and tourism topics varied by region.

· Co-occurrence of keywords to detect the main research topics and how these were interrelated.

· Evolution of thematic lines to observe how researchers’ approaches and concerns have changed over time.

Ethical considerations

Rigorous adherence to the ethical principles of research was maintained, ensuring correct attribution to the original authors of the works analyzed and respecting intellectual property rights.

Limitations

The methodology employed also considered the limitations inherent to any bibliometric study. These include the dependence on the keywords used for the search, which could limit the scope of the articles retrieved.(24,25) In addition, the analysis was restricted to data available in Scopus, which may not capture all relevant publications, especially those in less accessible databases or languages other than English.(26) Still, this methodological approach provided an in-depth and structured understanding of the existing literature on gentrification and tourism, offering valuable insights into the evolution of this field of study and its future directions.(27)

RESULTS

The bibliometric study on tourism gentrification based on the Scopus database from 2018 to 2023 revealed several important trends in this emerging field:

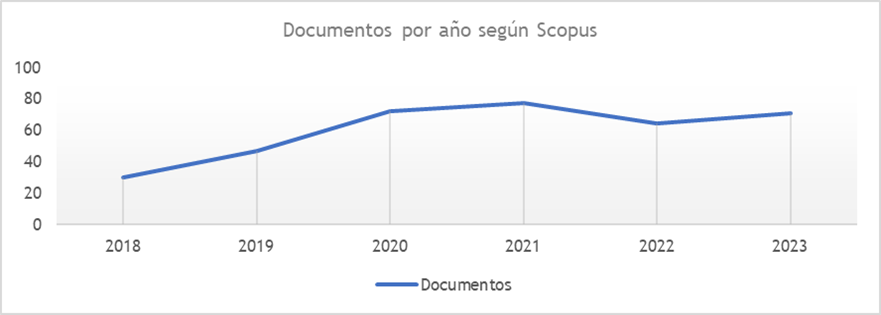

Increase in publications

There was an increase in the total number of publications on gentrification and tourism through 2021, followed by a decline in publications in 2022 and a further increase in 2023, although not reaching the 2021 total (figure 1). This indicates a growing academic interest in the intersection of these two topics since the end of the last decade and a relative trend towards stability. However, these findings need to be interpreted in terms of the impact of the pandemic on the tourism sector.

Figure 1. Documents per year according to the Scopus database

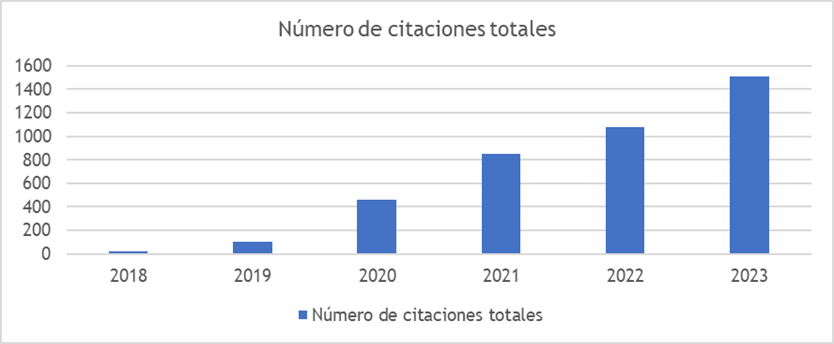

Citation trends

Publications related to gentrification and tourism showed an upward trend in citations, reflecting their relevance and growing impact on the research community (figure 2). In specific terms, 287 documents received a total of 5272 citations, which, from the perspective of the Hirch index for measuring the impact and relevance of scientific production, yielded an h-index of 39.

Figure 2. Papers per year according to the Scopus database

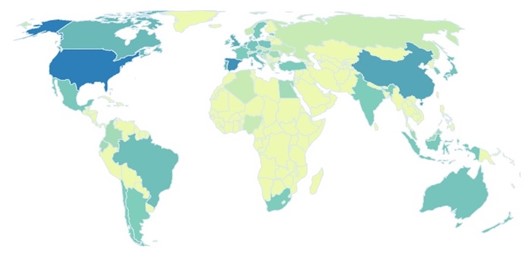

Geographical distribution

Research on gentrification and tourism was mainly concentrated in Europe and North America. However, significant studies were also identified in Asia and Latin America, showing a global interest in the effects of gentrification on the tourism sector (figure 3). The countries with at least ten publications, according to the Lens database, were the United States (94), Spain (73), China (48), United Kingdom (39), Portugal (26), Canada (25), Italy (22); Brazil (19); Netherlands (18); Japan (14); Australia (13); Germany (12), which confirmed the analysis performed.

Figure 3. Geographical distribution

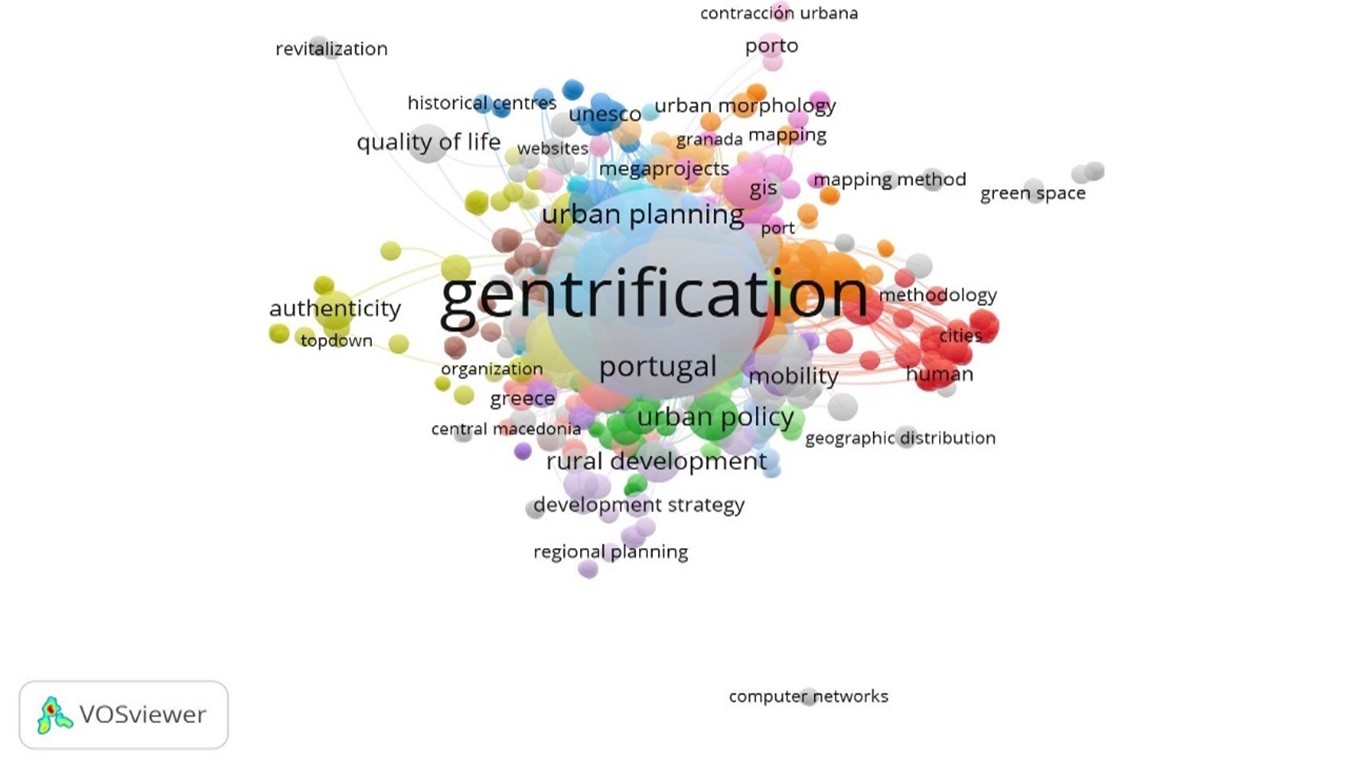

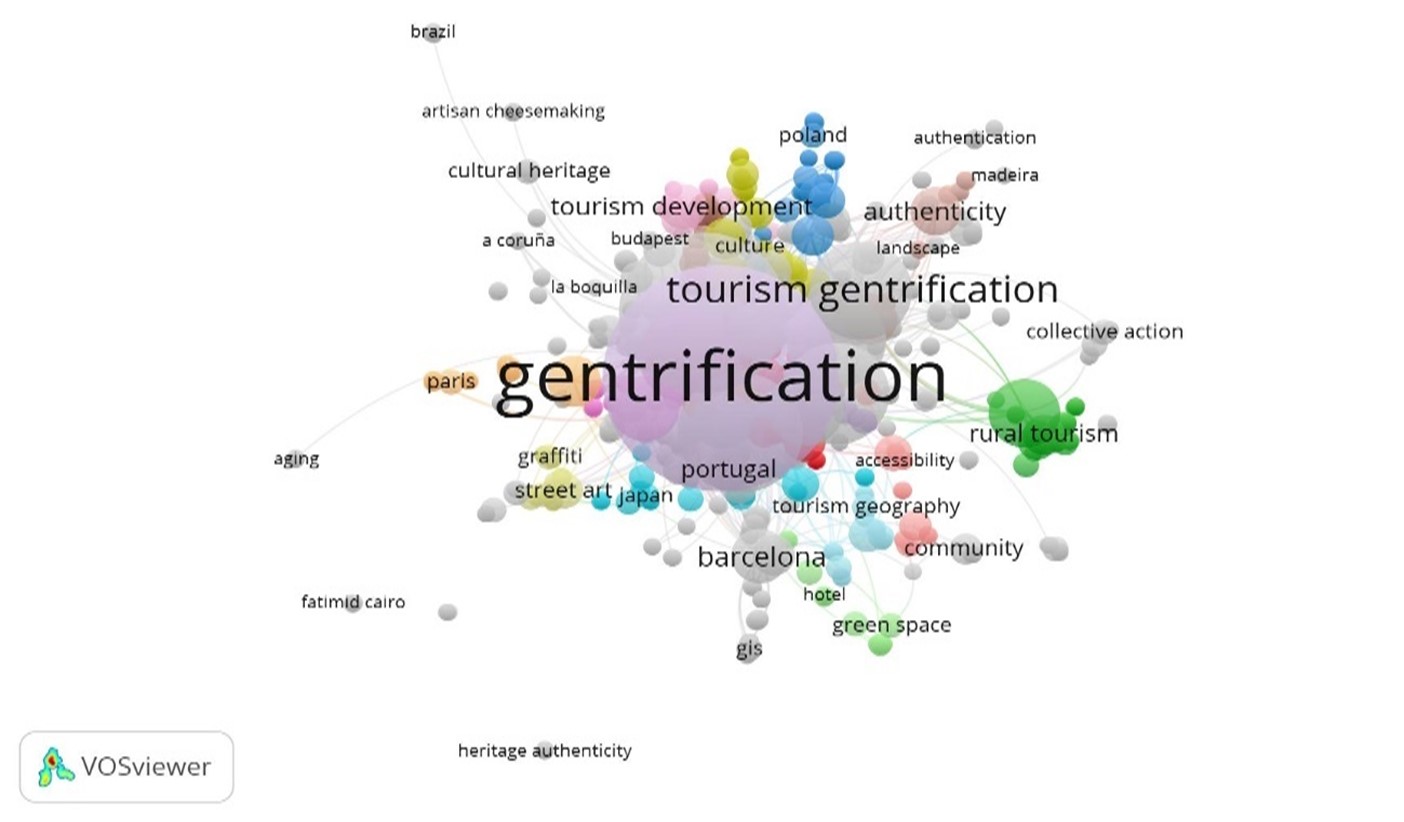

Keyword co-occurrence

The keyword co-occurrence analysis highlighted terms such as “mobility”, “sustainable development”, “regional development”, “social impact”, and “public policies” (figures 4 and 5). This underscored the focus on the social and economic consequences of gentrification on tourist communities.

Figure 4. Co-occurrence of all keywords

Figure 5. Co-occurrence of keywords designated by authors

Through this procedure, the main trends were clarified and contrasted with the areas most focused on studying the relationship between gentrification and tourism. This analysis showed that the most prominent fields are Social Sciences (n=292), Business (n=108) and Environmental Sciences (103). These fields were followed by some 14 disciplines that contributed between 48 and one publication (figure 6).

Figure 6. Main areas of expertise

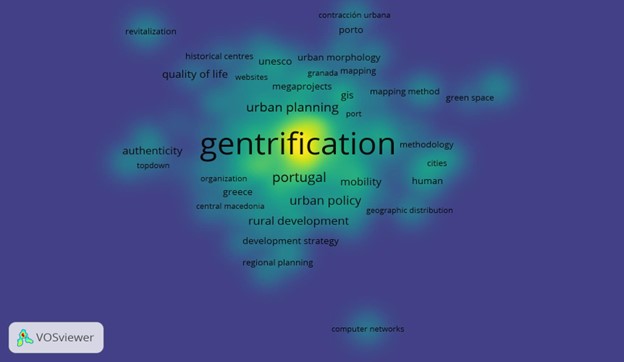

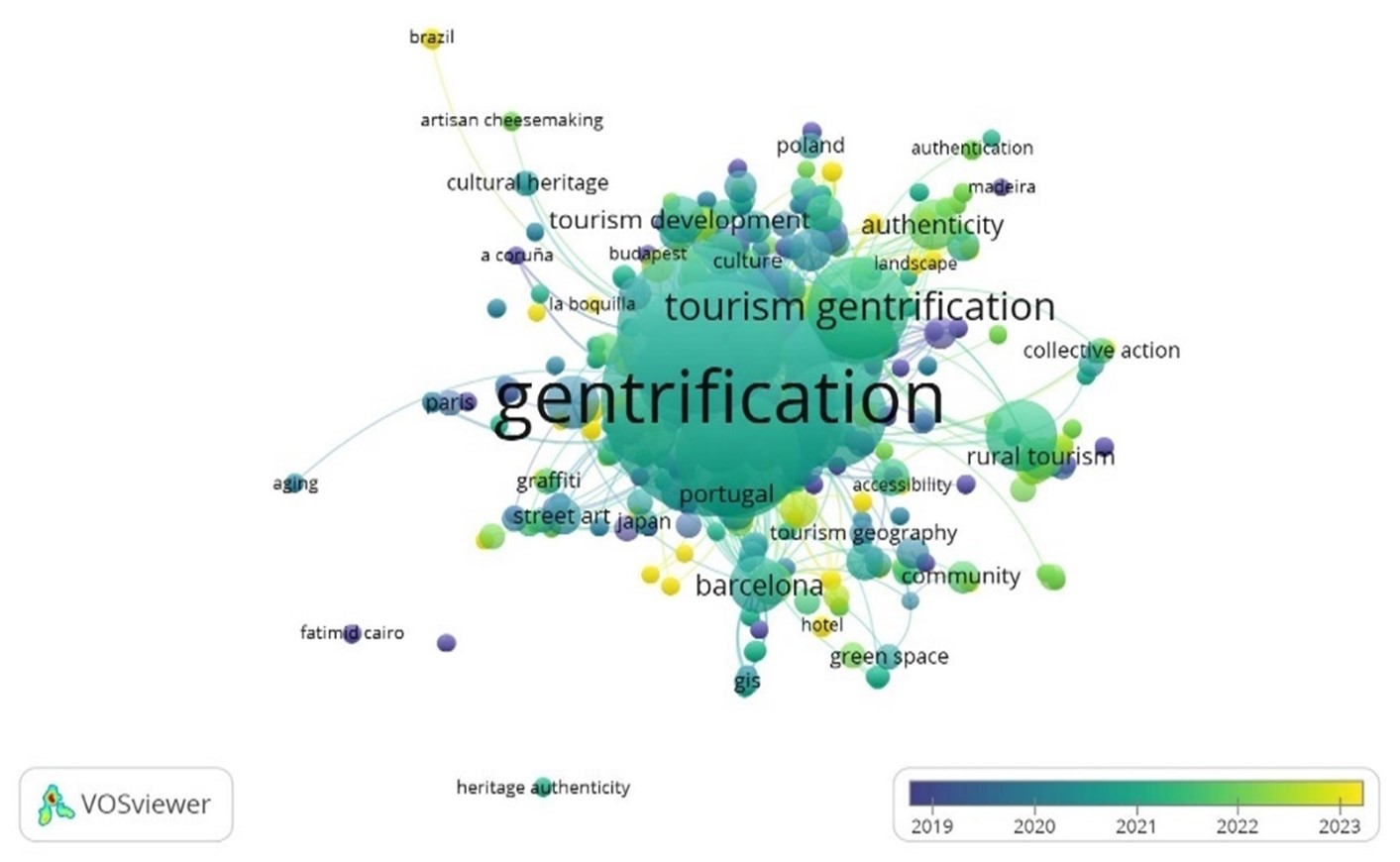

Evolution of the thematic lines

The analysis conducted in VOSviewer showed that the thematic lines evolved from focusing on economic impacts to a more holistic analysis that also considers the social and environmental aspects of gentrification in tourism destinations (figures 7 and 8). This review revealed the importance of addressing the multidimensional aspects of gentrification in the tourism context and highlighted the need for more inclusive policies that balance development and social equity.

Figure 7. Density visualization of all keywords

Figure 8. Thematic evolution based on the co-occurrence of keywords

Triangulation

To enrich the bibliometric analysis on tourism gentrification in the Scopus database between 2018 and 2023, new sources addressing complementary dimensions were integrated, and information was triangulated to provide a more comprehensive picture.

Additional studies indicated a growing focus on tourism sustainability within gentrification.(28,29,30) The literature showed that while some cities have used tourism to revitalize declining urban areas, this often resulted in the exclusion of residents and increased housing prices and services. These trends pose significant challenges in terms of social equity and access.(31,32)

One incorporated reference highlighted the relevance of urban and rural planning policies integrating gentrification and tourism considerations.(33,34) It was found that, in some cases, the implementation of responsible and participatory tourism strategies helped to mitigate the adverse effects of gentrification, promoting a more inclusive and sustainable development.(35,36,37)

The co-occurrence of keywords in the analyzed studies revealed an emerging interest in topics such as “health”,(38,39) “community participation”,(40,41,42) “cultural impact”(43,44) and “displacement”.(45,46,47) This finding suggests an evolution in the thematic line towards a more holistic approach that considers the economic impact of tourism and its social and cultural consequences.(48,49,50)

Regarding geographic distribution, the analysis reinforced that although research on gentrification and tourism is prominent in the Western world, there is a growing interest in exploring these phenomena in the context of developing countries. Therefore, it should be emphasized that the dynamics of gentrification differ significantly in these settings.(51,52,53,54)

Finally, triangulation of these results with previous studies and new references allowed the identification of critical areas for future research, such as the need to develop tourism models that equitably benefit all stakeholders involved, especially local communities more susceptible to gentrification’s negative impacts.(55,56,57,58) This extended analysis highlighted the importance of addressing the complex links between gentrification, tourism and sustainability to foster practices that promote fair and sustainable urban development.

DISCUSSION

The study identified several opportunities, challenges and barriers associated with the interaction between gentrification and tourism, addressing how these factors reshape urban and tourism dynamics.

Tourism gentrification presented significant opportunities for the revitalization of previously declining urban areas. Investment in tourism infrastructure, such as hotels, restaurants and cultural attractions, fostered increased economic activity and improved the image of previously marginalized destinations. These transformations often attracted a new profile of visitors and promoted more diverse and culturally enriching tourism. In addition, the urban renewal associated with tourism gentrification opened up new possibilities for local business development and job creation, contributing to the economic growth of local communities.

However, these processes were challenging. Tourism-driven gentrification also led to the displacement of low-income residents, who were often forced to leave their homes due to rising living and rental costs. This phenomenon exacerbated urban inequalities and generated tensions between new visitors and long-time residents. In addition, the rapid growth of the tourism sector in certain areas sometimes exceeds the capacity of existing infrastructure, leading to problems of utility overload and environmental degradation.

Among the main barriers identified was the lack of inclusive policies that balanced the benefits of tourism development with the protection of local communities. Insufficient regulation of real estate and tourism development allowed practices prioritizing economic gain over community well-being to flourish. In addition, the limited involvement of local communities in tourism planning and management often resulted in projects that needed to reflect their needs or interests.

To address these challenges and overcome barriers, future tourism gentrification policies and projects are suggested to adopt a more holistic and participatory approach. Integrating local communities in the initial planning and decision-making stages can foster developments that benefit all stakeholders. In addition, it is crucial to implement protective measures for vulnerable residents to prevent their displacement and ensure that gentrification does not lead to further social segregation.

The study highlighted the need for a stronger regulatory framework to guide tourism development sustainably and equitably, ensuring that tourism gentrification contributes positively to both the economy and social fabric of destinations. This would improve the sustainability of tourism destinations and enhance the quality of life for all city dwellers.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of the bibliometric study highlighted several key aspects related to the intersection of gentrification and tourism between 2018 and 2023. First, an increase in the number of publications and citations addressing gentrification in the tourism context was identified, reflecting a growing academic interest in this phenomenon. This interest indicated the relevance and urgency of understanding the dynamics that shape urban spaces and their implications for the tourism sector.

Secondly, the geographical distribution of the studies showed a significant concentration in European and North American regions, although there was also an emerging focus on Asia and Latin America. This trend underscored the need to expand research to more varied contexts to gain a more global and diversified perspective on how gentrification affects different tourism destinations worldwide.

In addition, keyword co-occurrence analysis focused on sustainability, social impact, and public policy. These themes highlighted contemporary concerns about ensuring that tourism development’s benefits are distributed equitably and mitigating negative effects such as displacement of local residents.

Finally, there was an evolution in the thematic strands from a predominantly economic approach to a more integrated analysis that includes social and environmental considerations. This shift suggests recognizing the complexity of tourism and gentrification and the need to address these phenomena with multidisciplinary approaches and informed policies.

These findings emphasize the importance of further research and debate on tourism gentrification to understand its multiple dimensions and effects better and develop strategies to promote more inclusive and sustainable tourism.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1. Pieroni R, Naef PJ. Exploring new frontiers? “Neo-slumming” and gentrification as a tourism resource. International Journal of Tourism Cities. 2019;5(3):338–53. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-01-2018-0008

2. Kent‐Stoll P. The racial and colonial dimensions of gentrification. Sociology Compass. 2020;14(12):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12838

3. Ocejo RE, Kosta EB, Mann A. Centering Small Cities for Urban Sociology in the 21st Century. City & Community. 2020;19(1):3–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12484

4. Blok A. Urban green gentrification in an unequal world of climate change. Urban Studies. 2020;57(14):2803–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019891050

5. Hübscher M. Megaprojects, Gentrification, and Tourism. A Systematic Review on Intertwined Phenomena. Sustainability. 2021;13(22):12827. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212827

6. Torres Barreto ML. Estudio de casos de éxito y fracaso de emprendedores a raíz del COVID-19 en Bucaramanga y su área metropolitana. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202332. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202332

7. Cocola-Gant A, Lopez-Gay A. Transnational gentrification, tourism and the formation of ‘foreign only’ enclaves in Barcelona. Urban Studies. 2020;57(15):3025–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020916111

8. Cocola-Gant A, Gago A, Jover J. Tourism, Gentrification and Neighbourhood Change: An Analytical Framework– Reflections from Southern European Cities. In: Oskam JA, editor. The Overtourism Debate. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2020. p. 121–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83867-487-820201009

9. Tolfo G, Doucet B. Gentrification in the media: the eviction of critical class perspective. Urban Geography. 2021;42(10):1418–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1785247

10. Liu C, Deng Y, Song W, Wu Q, Gong J. A comparison of the approaches for gentrification identification. Cities. 2019;95:102482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102482

11. González-Pérez JM. The dispute over tourist cities. Tourism gentrification in the historic Centre of Palma (Majorca, Spain). Tourism Geographies. 2020;22(1):171–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1586986

12. González Ávila DIN, Garzón Salazar DP, Sánchez Castillo V. Cierre de las empresas del sector turismo en el municipio de Leticia: una caracterización de los factores implicados. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202342. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202342

13. Valle MM. Globalizing the Sociology of Gentrification. City & Community. 2021;20(1):59–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12507

14. Valente R, Russo AP, Vermeulen S, Milone FL. Tourism pressure as a driver of social inequalities: a BSEM estimation of housing instability in European urban areas. European Urban and Regional Studies. 2022;29(3):332–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764221078729

15. Preis B, Janakiraman A, Bob A, Steil J. Mapping gentrification and displacement pressure: An exploration of four distinct methodologies. Urban Studies. 2021;58(2):405–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020903011

16. Sanabria Martínez MJ. Construir nuevos espacios sostenibles respetando la diversidad cultural desde el nivel local. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):20222. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc20222

17. Milano C, González-Reverté F, Benet Mòdico A. The social construction of touristification. Residents’ perspectives on mobilities and moorings. Tourism Geographies. 2023;25(4):1273–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2022.2150785

18. Torres Outón SM. Gentrification, touristification and revitalization of the Monumental Zone of Pontevedra, Spain. International Journal of Tourism Cities. 2019;6(2):347–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-08-2018-0059

19. Tápanes Suárez E, Bosch Nuñez O, Sánchez Suárez Y, Marqués León M, Santos Pérez O. Sistema de indicadores para el control de la sostenibilidad de los centros históricos asociada al transporte. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202352. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202352

20. Linnenluecke MK, Marrone M, Singh AK. Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Australian Journal of Management. 2020;45(2):175–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219877678

21. Gan Y, He Q, Li C, Alsharafi BLM, Zhou H, Long Z. A bibliometric study of the top 100 most-cited papers in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Frontiers in Oncology. 2023;13:1146515. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1146515

22. Ledesma F, Malave González BE. Patrones de comunicación científica sobre E-commerce: un estudio bibliométrico en la base de datos Scopus. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):202214. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202214

23. Snyder H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research. 2019;104:333–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

24. Adegoriola MI, Lai JHK, Chan EH, Darko A. Heritage building maintenance management (HBMM): A bibliometric-qualitative analysis of literature. Journal of Building Engineering. 2021;42:102416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102416

25. Deng W, Liang Q, Li J, Wang W. Science mapping: a bibliometric analysis of female entrepreneurship studies. Gender in Management: An International Journal. 2021;36(1):61–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-12-2019-0240

26. Ejaz H, Zeeshan HM, Ahmad F, Bukhari SNA, Anwar N, Alanazi A, et al. Bibliometric Analysis of Publications on the Omicron Variant from 2020 to 2022 in the Scopus Database Using R and VOSviewer. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(19):12407. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912407

27. Anggadwita G, Indarti N. Women entrepreneurship in the internationalization of SMEs: a bibliometric analysis for future research directions. European Business Review. 2023;35(5):763–96. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-01-2023-0006

28. Nickayin SS, Halbac-Cotoara-Zamfir R, Clemente M, Chelli FM, Salvati L, Benassi F, et al. “Qualifying Peripheries” or “Repolarizing the Center”: A Comparison of Gentrification Processes in Europe. Sustainability. 2020;12(21):9039. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219039

29. Fernández Hernández A, Bravo Benítez E. Potencialidad del nearshoring para el desarrollo económico de México. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):2023105. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2023105

30. Agyeiwaah E. Over-tourism and sustainable consumption of resources through sharing: the role of government. International Journal of Tourism Cities. 2019;6(1):99–116. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-06-2019-0078

31. Araque Geney EA. Una mirada a la realidad económica y educativa de la mujer indígena Zenú: reflexiones desde el Cabildo Menor el Campo Mirella. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):202366. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202366

32. Lo JSK, McKercher B. Tourism gentrification and neighbourhood transformation. International Journal of Tourism Cities. 2023;9(4):923–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-03-2023-0038

33. Phillips M, Smith D, Brooking H, Duer M. Re-placing displacement in gentrification studies: Temporality and multi-dimensionality in rural gentrification displacement. Geoforum. 2021;118:66–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.12.003

34. López‐Gay A, Cocola‐Gant A, Russo AP. Urban tourism and population change: Gentrification in the age of mobilities. Population Space and Place. 2021;27(1):e2380. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2380

35. Tulumello S, Allegretti G. Articulating urban change in Southern Europe: Gentrification, touristification and financialisation in Mouraria, Lisbon. European Urban and Regional Studies. 2021;28(2):111–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776420963381

36. Um J, Yoon S. Evaluating the relationship between perceived value regarding tourism gentrification experience, attitude, and responsible tourism intention. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change. 2021;19(3):345–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2019.1707217

37. Acero Moreno AM, Ordoñez Paredes BA, Toloza Guardias HP, Vega Palmera B. Análisis estratégico para la empresa Imbocar, seccional Valledupar – Colombia. Región Científica. 2023;2:202395. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202395

38. Sánchez-Ledesma E, Vásquez-Vera H, Sagarra N, Peralta A, Porthé V, Díez È. Perceived pathways between tourism gentrification and health: A participatory Photovoice study in the Gòtic neighborhood in Barcelona. Social Science & Medicine. 2020;258:113095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113095

39. Smith GS, Breakstone H, Dean LT, Thorpe RJ. Impacts of Gentrification on Health in the US: a Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Urban Health. 2020;97(6):845–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-020-00448-4

40. Zhao Z, Wang Y, Ou Y, Liu L. Between Empowerment and Gentrification: A Case Study of Community-Based Tourist Program in Suichang County, China. Sustainability. 2022;14(9):5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095187

41. Mullenbach LE, Baker BL. Environmental Justice, Gentrification, and Leisure: A Systematic Review and Opportunities for the Future. Leisure Sciences. 2020;42(5–6):430–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2018.1458261

42. Domínguez-Mujica J, González-Pérez JM, Parreño-Castellano JM, Sánchez-Aguilera D. Gentrification on the Move. New Dynamics in Spanish Mature Urban-Tourist Neighborhoods. Urban Science. 2021;5(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci5010033

43. Linz J. Where crises converge: the affective register of displacement in Mexico City’s post-earthquake gentrification. Cultural Geographies. 2021;28(2):285–300. https://doi.org/

44. Novy J. Urban tourism as a bone of contention: four explanatory hypotheses and a caveat. International Journal of Tourism Cities. 2019;5(1):63–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-01-2018-0011

45. Versey HS. A tale of two Harlems: Gentrification, social capital, and implications for aging in place. Social Science & Medicine. 2018;214:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.024

46. Delmelle EC. Transit-induced gentrification and displacement: The state of the debate. In: Advances in Transport Policy and Planning. Elsevier; 2021. p. 173–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.atpp.2021.06.005

47. Easton S, Lees L, Hubbard P, Tate N. Measuring and mapping displacement: The problem of quantification in the battle against gentrification. Urban Studies. 2020;57(2):286–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019851953

48. Gravari-Barbas M, Jacquot S, Cominelli F. New cultures of urban tourism. International Journal of Tourism Cities. 2019;5(3):301–6. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-09-2019-160

49. Elorrieta B, Cerdan Schwitzguébel A, Torres-Delgado A. From success to unrest: the social impacts of tourism in Barcelona. International Journal of Tourism Cities. 2022;8(3):675–702. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-05-2021-0076

50. Chamizo-Nieto FJ, Nebot-Gómez De Salazar N, Rosa-Jiménez C, Reyes-Corredera S. Touristification and Conflicts of Interest in Cruise Destinations: The Case of Main Cultural Tourism Cities on the Spanish Mediterranean Coast. Sustainability. 2023;15(8):6403. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086403

51. Jiménez-Pitre I, Molina-Bolívar G, Gámez Pitre R. Visión sistémica del contexto educativo tecnológico en Latinoamérica. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202358. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202358

52. Jover J, Díaz-Parra I. Gentrification, transnational gentrification and touristification in Seville, Spain. Urban Studies. 2020;57(15):3044–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019857585

53. Sigler T, Wachsmuth D. New directions in transnational gentrification: Tourism-led, state-led and lifestyle-led urban transformations. Urban Studies. 2020;57(15):3190–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020944041

54. Lorenzen M. Rural gentrification, touristification, and displacement: Analysing evidence from Mexico. Journal of Rural Studies. 2021;86:62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.05.015

55. Zmyślony P, Leszczyński G, Waligóra A, Alejziak W. The Sharing Economy and Sustainability of Urban Destinations in the (Over)tourism Context: The Social Capital Theory Perspective. Sustainability. 2020;12(6):2310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062310

56. Ripoll Rivaldo M. El emprendimiento social universitario como estrategia de desarrollo en personas, comunidades y territorios. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):202379. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202379

57. Robertson D, Oliver C, Nost E. Short-term rentals as digitally-mediated tourism gentrification: impacts on housing in New Orleans. Tourism Geographies. 2022;24(6–7):954–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1765011

58. Rubin CL, Chomitz VR, Woo C, Li G, Koch-Weser S, Levine P. Arts, Culture, and Creativity as a Strategy for Countering the Negative Social Impacts of Immigration Stress and Gentrification. Health Promotion Practice. 2021;22(1_suppl):131S-140S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839921996336

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Chris Nathalie Aristizábal Valbuena.

Data curation: Chris Nathalie Aristizábal Valbuena.

Formal analysis: Chris Nathalie Aristizábal Valbuena.

Drafting - original draft: Chris Nathalie Aristizábal Valbuena.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Chris Nathalie Aristizábal Valbuena.