doi: 10.62486/gen202453

REVIEW

Gentrified Humanities? An analysis of the main trends in the Scopus database

¿Humanidades gentrificadas? Un análisis de las principales tendencias en la base de datos Scopus

Rogelio Jiménez Zapata1

![]() *

*

1Universidad Santo Tomas. Bogotá, Colombia.

Cite as: Jiménez Zapata R. Gentrified Humanities? An analysis of the main trends in the Scopus database. Gentrification. 2024; 2:53. https://doi.org/10.62486/gen202453

Submitted: 17-06-2023 Revised: 20-09-2023 Accepted: 08-01-2024 Published: 05-01-2024

Editor: Estela

Hernández-Runque ![]()

Corresponding Author: Rogelio Jiménez Zapata *

ABSTRACT

The present bibliometric study examines the evolution and impact of gentrification within the humanities field. Using the Scopus and Lens databases, and through the VOSviewer software, documents, citations, areas and types of publication, keyword co-occurrence, and geographical distribution related to gentrification were analyzed. The results indicate a predominant concentration of research in Europe and North America, highlighting the need to geographically diversify the academic focus. Furthermore, an increasing thematic diversity and an interdisciplinary approach in the studies were observed, expanding the understanding of the phenomenon beyond its economic and social impacts to include cultural and identity aspects. The study also identified key works that have significantly shaped the academic discourse on gentrification in the humanities, highlighting established and emerging areas of study. These findings emphasize the importance of expanding bibliometric research to address gaps and foster a more complete understanding of the impact of gentrification.

Keywords: Cultural Impact; Community Displacement; Urban Transformation; Identity and Gentrification; Socioeconomic Dynamics.

RESUMEN

El presente estudio bibliométrico examina la evolución y el impacto de la gentrificación dentro del campo de las humanidades. Utilizando las bases de datos Scopus y Lens, y mediante el software VOSviewer, se analizaron los documentos, citas, áreas y tipos de publicación, co-ocurrencia de palabras clave y distribución geográfica relacionados con la gentrificación. Los resultados indican una concentración predominante de investigaciones en Europa y América del Norte, destacando la necesidad de diversificar geográficamente el enfoque académico. Además, se observó una creciente diversidad temática y un enfoque interdisciplinario en los estudios, expandiendo la comprensión del fenómeno más allá de sus impactos económicos y sociales para incluir aspectos culturales e identitarios. El estudio también identificó trabajos clave que han moldeado significativamente el discurso académico sobre la gentrificación en las humanidades, subrayando áreas de estudio consolidadas y emergentes. Estas conclusiones enfatizan la importancia de ampliar la investigación bibliométrica para abordar brechas y fomentar un entendimiento más completo del impacto de la gentrificación.

Palabras clave: Impacto Cultural; Desplazamiento Comunitario; Transformación Urbana; Identidad y Gentrificación; Dinámicas Socioeconómicas.

INTRODUCTION

In the last decade, gentrification has positioned itself as one of the most debated and studied urban phenomena, both for its ability to revitalize degraded urban areas and its implications for the Displacement of vulnerable populations.(1,2) This process, transforming low-income sectors into enclaves of higher economic and cultural value, presents unique challenges and opportunities for modern cities.(3,4) As gentrification progresses, not only a change in physical infrastructure is observed, but also a transformation in the cultural and social landscape of neighbourhoods.(5,6,7)

Academic studies on gentrification have proliferated, exploring its impacts in diverse spheres such as economics,(8,9,10) sociology(11,12,13) and urbanism.(14,15) However, the field of humanities has yet to be explored in the same depth, even though culture and identity are central elements in the gentrification process. Humanities research offers a critical lens for understanding how gentrification affects the cultural life of cities and how cultural expressions can, in turn, influence the course of gentrification.(16,17,18,19)

Given the complexity and multidimensionality of the phenomenon, it is essential to address how gentrification has been treated in research within the humanities. Bibliometric analysis emerges as a fundamental tool for this purpose, allowing us to identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing literature.(20,21) Through this approach, we can map the main areas of study, assess the evolution of the academic dialogue, and highlight new research directions.(22,23,24)

Therefore, this bibliometric study is crucial to understanding the current state of gentrification research in the humanities and identifying underrepresented areas that require scholarly attention. Furthermore, it aims to provide a solid foundation for future research, helping to design studies that address the critical intersections between gentrification, culture, and society, a critical aspect noted in the literature on the subject.(25) Thus, this research not only contributes to the academic body but also informs policymakers and cultural activists on how to address the effects of gentrification in a way that benefits all urban communities.(26)

Fundamental concepts

The theoretical framework of gentrification encompasses several key concepts that facilitate understanding this complex and multifaceted phenomenon. The main terms used in the study of gentrification are defined below:

Gentrification

Gentrification refers to the transformation process of a neighbourhood with low incomes and a deteriorated physical environment through the arrival of residents of higher socioeconomic status. This demographic change is often accompanied by housing renovation, increases in property values, and changes in the character and culture of the neighbourhood.(27) Gentrification often results in the Displacement of the original residents, who cannot bear the increased cost of living.(28,29)

Displacement

A direct consequence of gentrification is that long-time residents, usually of lower income, are forced to move due to rising rents and cost of living, as well as the transformation of their environment’s social and cultural fabric.(30,31) Displacement can be physical, when people move out of their homes, or economic when they can no longer afford to live in their neighbourhood due to rising costs.(32,33)

Cultural capital

This term describes the non-economic resources, such as knowledge, skills, education, and advantages that individuals possess, which enable them to gain power and status in society.(34,35) In the context of gentrification, newcomers often bring high cultural capital, which can alter neighbourhood dynamics and identity.(36,37)

Urban renewal

Often confused with gentrification, urban renewal involves planned interventions by the state or developers to improve and revitalize urban areas that are physically deteriorated.(38,39) Although renewal may be part of gentrification, it does not always involve demographic change or Displacement.(40,41,42)

Urban transformation

This refers to broad changes in the structure and character of urban areas, which may include gentrification and other types of development and socioeconomic change.(43,44)

These concepts form the basis for exploring how gentrification impacts not only the economy and demographics of an area but also its culture and social fabric.(45) The study of these terms and their interaction is crucial to a full understanding of the phenomenon of gentrification and its effects on urban communities.

METHOD

A comprehensive methodological design was used for the bibliometric study to explore the evolution of documents, citations received, areas and types of publication, co-occurrence of keywords and geographical distribution of studies on gentrification in the humanities. The research was based on data extracted from the Scopus and Lens databases, recognized for broad coverage of academic and scientific literature.

Initially, a search for terms related to gentrification in the humanities was conducted in both databases. The inclusion criterion focused on documents that explicitly addressed the topic of gentrification within the humanities framework. Hence, the filter (LIMIT TO) was employed. To obtain a representative view of the existing literature, documents were analyzed by type, including journal articles, conference papers, and book chapters.

Subsequently, VOSviewer software was used for keyword co-occurrence analysis, which allowed the identification of the main themes and trends within the selected corpus. VOSviewer also facilitated the visualization of collaborative networks between countries, while the geographical distribution of publications was analyzed in Lens. This provided insight into the global and regional scope of gentrification studies.

In addition, the evolution of papers over time was analyzed to observe trends in publication and scholarly impact by analyzing the citations received. This approach made it possible to discern the fundamental works in the field and to evaluate the influence of different currents of thought within the topic of study.

Finally, the findings were synthesized to highlight emerging lines of research and areas requiring further attention. This analysis provided a solid foundation for future research and the development of policy and practice informed by scholarly evidence in humanities and gentrification.

RESULTS

In the descriptive bibliometric analysis conducted on gentrification in the humanities, using the Scopus database, several key trends in the existing literature were identified. First, an increase in the number of publications dealing with gentrification within the environmental sciences was observed, highlighting a significant annual growth in this field since 1987, underscoring a growing interest in exploring the interactions between gentrification processes and environmental issues.

However, when filtering the search period, an intermittent trend was observed regarding total annual publications. It was observed in the distribution that the total number of publications increased and then decreased throughout the decade studied, except in 2018 and 2023. In contrast, the relevance of the field showed a growth trend, which was measured by analyzing the pattern of citations, which, unlike the papers, climbed steadily over the period with 556 papers cited, 5480 citations, an h-index of 33 (figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparative graph document/citations

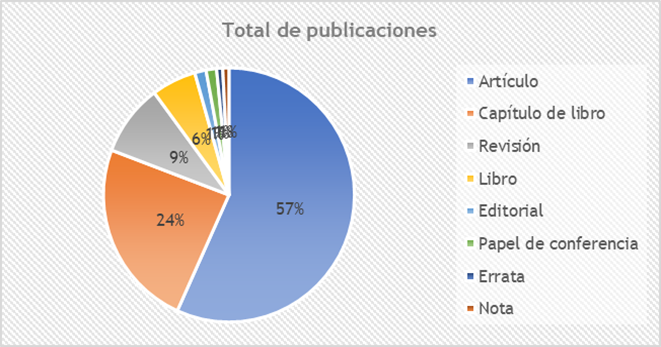

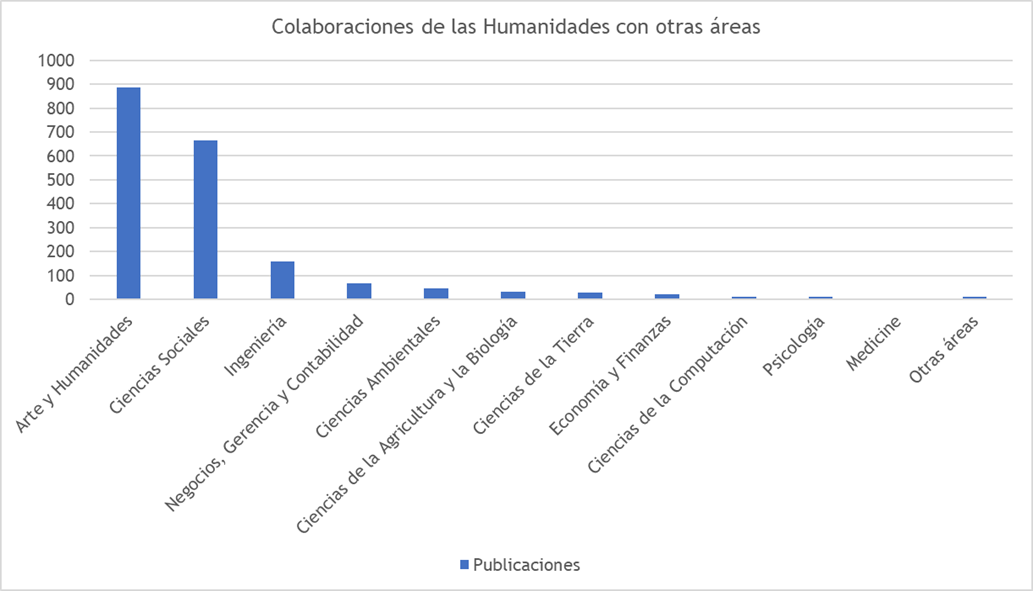

Regarding publication practices in the humanities, journal articles and book chapters were the most common channels. However, reviews also play a crucial role, especially in disciplines such as religion, philosophy and literature (figure 2). As for the areas with which collaborations were established, the social sciences and engineering stood out, with the rest of the disciplines coded by the base being unrepresentative (figure 3).

Figure 2. Publications by type

Figure 3. Collaborations by discipline

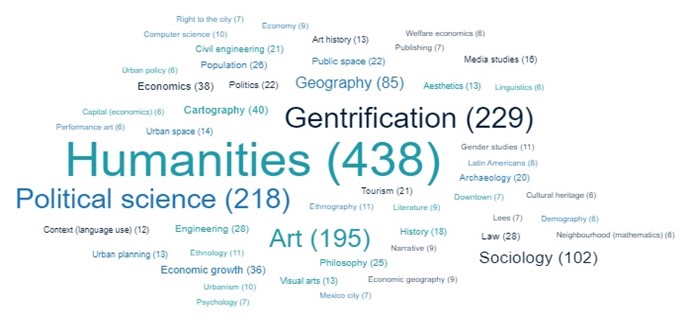

These findings suggest a diversity in citation and publication practices, where ancient literature and primary sources are frequently used, reflecting a less focused approach to immediate current affairs than in other sciences. To contrast these results, the analysis was replicated in the Lens database, allowing us to look at other fields, such as political science, geography, aesthetics, and cartography (figure 4).

Figure 4. Most relevant fields according to Lens

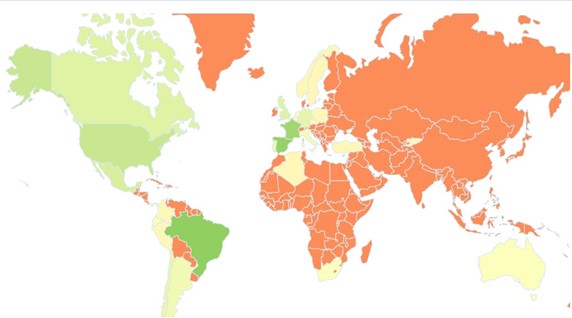

In addition, persistence in using sources in languages other than English was noted, especially in literary and social science studies, which poses challenges for databases that predominantly index sources in English. This indicates the need for bibliometric methodologies considering the rich linguistic diversity and publishing practices in the humanities. As seen in the map of publications (figure 5), the greatest production is concentrated in the global North. However, after filtering, it was possible to appreciate the field’s emergence in countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Ecuador and Colombia.

Figure 5. Global map of publications

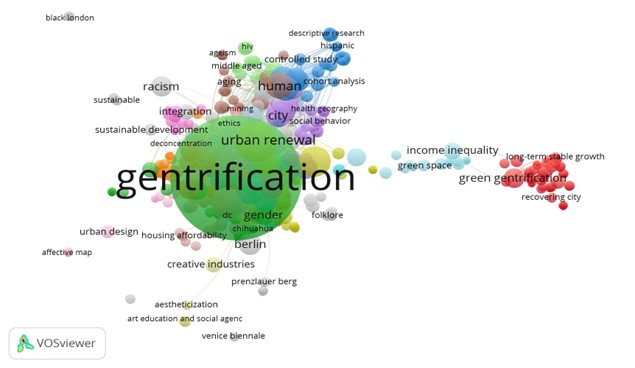

Regarding keywords, the co-occurrence showed two major clusters, the first formed by seven clusters and the second, of lesser relevance, by two (figure 6). The two clusters of lesser importance showed a concentrated interest in social and sustainability issues. On the other hand, although several lines were overlapping in the remaining seven clusters, the use of terms from the humanities could have been more directly apparent; rather, the emphasis was on the social sciences, which contradicts what was revealed by the databases analyzed. This may suggest the need to analyze the keyword selection practices of journals and indexers.

Figure 6. Co-occurrence network

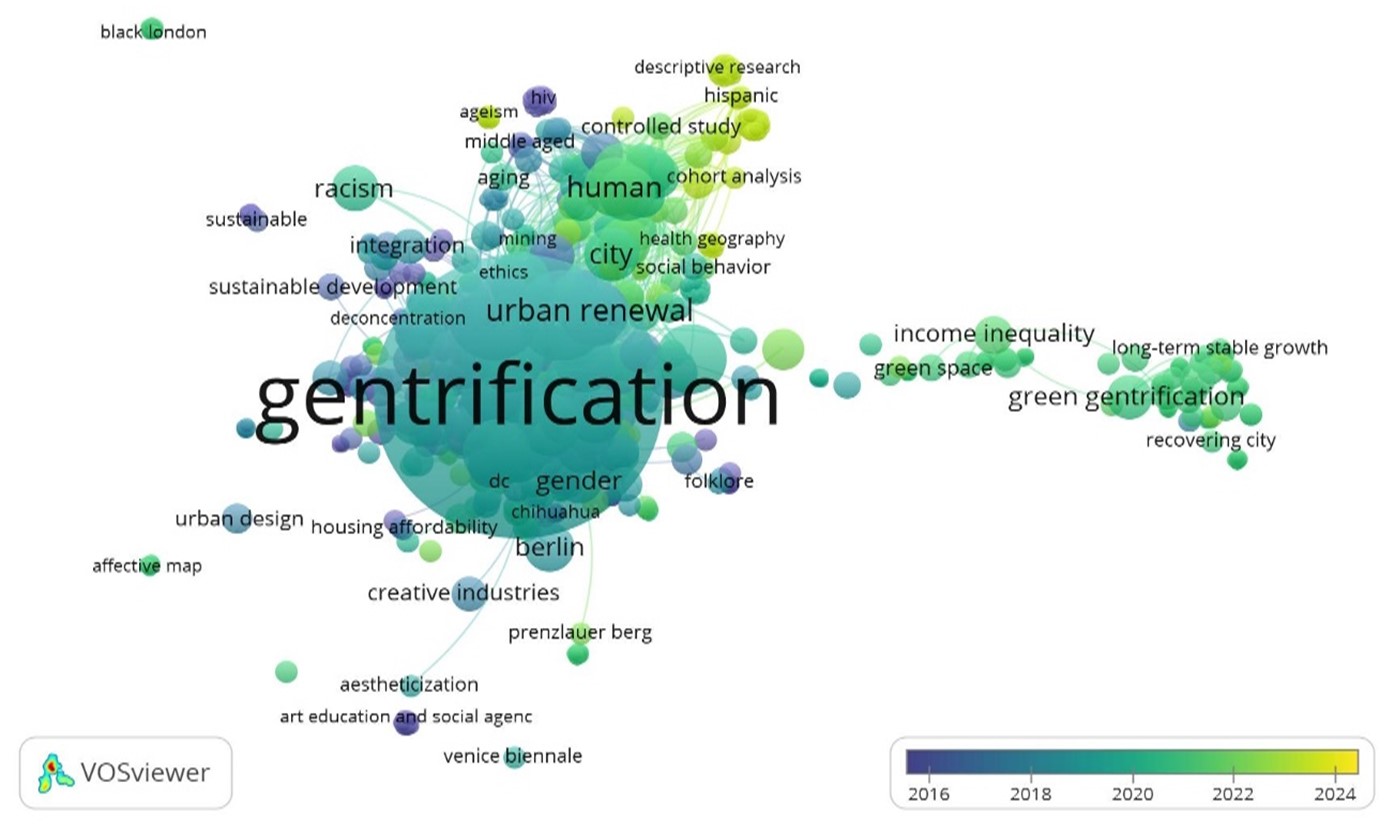

Regarding evolution, the VOSviewer showed a trend from folklore studies, art education and agency towards descriptive research, racial and gender studies, ageing and other issues that, although not recent, have gained visibility. On the other hand, at the beginning of the decade, interest remained in studies directly associated with gentrification, the urban environment and renovation (figure 7).

Figure 7. Evolution of the lines according to the co-occurrence of keywords

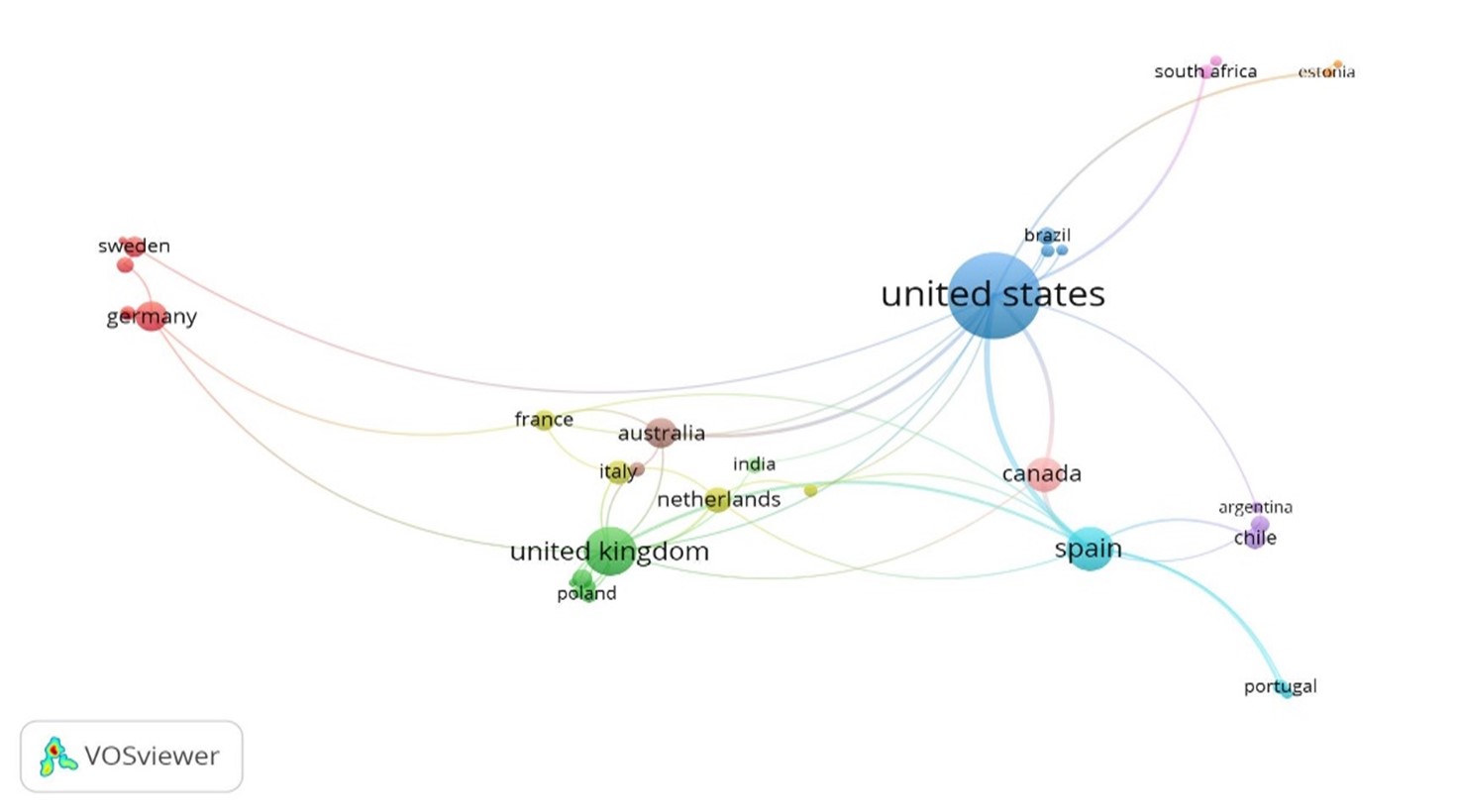

Finally, the collaboration networks between countries showed that the countries with the most links in the period were the United States, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Although Ibero-American countries such as Portugal, Brazil, Chile and Argentina (in addition to Spain above) stand out in these collaborative networks, it can be seen that the networks are not strong enough, and this could mark an important direction for the future development of the field (figure 8).

Figure 8. Collaboration networks between countries

These trends highlight the evolution of the humanities and suggest future lines of research that could focus on analyzing how publishing practices in the humanities respond to pressures for research outputs and how this might influence changing practices within this academic field.

Expanded Analysis

The expanded analysis identified several notable trends and developments. For example, recent studies have explored how gentrification can influence crime reduction in urban areas while emphasizing that this process should not ignore vulnerable populations. This multiperspective approach to gentrification brings a more nuanced understanding of its effects on the community, highlighting the importance of considering both benefits and potential negative consequences.

In addition, interest has emerged in how renewable energy communities are being driven by European Union legislation, reflecting dynamic growth in this sector and exponential investment in technologies such as photovoltaic and energy storage systems. This field offers an interesting parallel with studies on gentrification since both topics are intertwined with urban transformation and development.

The bibliometric methodology applied to these topics is evolving rapidly as well. Modern bibliometric techniques include citation network analysis and semantic approaches, allowing for a better understanding of the interactions and evolution of disciplines. In addition, including a wider range of bibliometric sources and methodologies designed specifically for the humanities makes it possible to more adequately capture the diversity of publications and citations in these areas.

Thus, future studies might consider how these trends in gentrification research connect to broader social and economic changes and how bibliometric methodologies can be adapted or expanded to capture the rich diversity of the humanities better. This will enrich the field and contribute to a broader scholarly dialogue on the implications of gentrification in the humanities disciplines.

DISCUSSION

In discussing gentrification in the humanities, it is crucial to identify and propose future lines of research, considering both current challenges and emerging opportunities.(46,47) One of the main areas of future interest is assessing the impact of gentrification on local communities, especially in terms of cultural and educational accessibility in revitalized urban areas.(48,49,50) Future research could explore how cultural and educational initiatives can serve as tools asto para mitigar los aspectos negativos de la gentrificación como para fomentar la inclusión social.

Challenges in this field include obtaining longitudinal data that allow for a detailed analysis of long-term social and cultural transformations.(51) In addition, the subjectivity inherent in the definition and perception of gentrification can complicate the comparability of studies and the generalization of results. Establishing clear and consistent methodological frameworks that allow for comparative studies across different regions and cultural contexts is essential.(52)

In the Latin American context, gentrification presents particular characteristics due to the region’s specific urban and socioeconomic dynamics.(53,54,55) For example, in several Latin American cities, gentrification processes are often intertwined with problems of displacement and urban segregation, raising critical questions about equity and social justice.(56,57) Future research could focus on how urban and housing policies influence these processes and on strategies that governments and communities can employ to ensure that neighbourhood revitalization does not exclude the original inhabitants.(58)

Finally, researchers must address how cultural differences affect the experience and consequences of gentrification in Latin America, exploring in depth how local identity and culture can be preserved and valued amid rapid urban change. These approaches will enrich the academic understanding of gentrification and inform more effective and culturally sensitive public policies.

CONCLUSIONS

It was found that most studies on gentrification in the humanities were concentrated in Europe and North America. This phenomenon reflected the uneven distribution of scholarly focus and resources, suggesting the need to expand research to other regions to gain a more global and diverse perspective on the impact of gentrification on local communities.

The research revealed a growth in thematic diversity and the adoption of interdisciplinary approaches over time. Studies addressed the economic and social impacts of gentrification and its relationship to cultural identity and heritage, highlighting the field’s evolution towards a more holistic understanding of gentrification.

Several key works were identified that have been widely cited and significantly influenced the humanities gentrification research. This underscores the importance of certain seminal studies in shaping academic discourse and suggests consolidated and emerging areas of study within the field.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1. Hatz G. Can public subsidized urban renewal solve the gentrification issue? Dissecting the Viennese example. Cities. 2021;115:103218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103218

2. Yazar M, Hestad D, Mangalagiu D, Saysel AK, Ma Y, Thornton TF. From urban sustainability transformations to green gentrification: urban renewal in Gaziosmanpaşa, Istanbul. Climatic Change. 2020;160(4):637–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02509-3

3. Cole HVS, Mehdipanah R, Gullón P, Triguero-Mas M. Breaking Down and Building Up: Gentrification, Its drivers, and Urban Health Inequality. Current Environmental Health Reports. 2021;8(2):157–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-021-00309-5

4. Gou F, Zhai W, Wang Z. Visualizing the Landscape of Green Gentrification: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Directions. Land. 2023;12(8):1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12081484

5. Verlaan T, Hochstenbach C. Gentrification through the ages: A long-term perspective on urban displacement, social transformation and resistance. City. 2022;26(2–3):439–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2022.2058820

6. Pérez Guedes N, Arufe Padrón A. Perspectivas de la transición energética en Latinoamérica en el escenario pospandemia. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202334. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202334

7. Sutherland LA. Horsification: Embodied gentrification in rural landscapes. Geoforum. 2021;126:37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.07.020

8. Almeida R, Patrício P, Brandão M, Torres R. Can economic development policy trigger gentrification? Assessing and anatomising the mechanisms of state-led gentrification. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. 2022;54(1):84–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211050076

9. Afanador Cubillos N. Historia de la producción y sus retos en la era actual. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202315. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202315

10. Moos M, Revington N, Wilkin T, Andrey J. The knowledge economy city: Gentrification, studentification and youthification, and their connections to universities. Urban Studies. 2019;56(6):1075–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017745235

11. Amorim Maia AT, Calcagni F, Connolly JJT, Anguelovski I, Langemeyer J. Hidden drivers of social injustice: uncovering unequal cultural ecosystem services behind green gentrification. Environmental Science & Policy. octubre de 2020;112:254–63. https://doi.org/

12. Valle MM. Globalizing the Sociology of Gentrification. City & Community. 2021;20(1):59–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12507

13. Clerval A. Gentrification and social classes in Paris, 1982-2008. Urban Geography. 2022;43(1):34–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1826728

14. Zhan Y. Beyond neoliberal urbanism: Assembling fluid gentrification through informal housing upgrading programs in Shenzhen, China. Cities. 2021;112:103111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103111

15. Bolzoni M, Semi G. Adaptive urbanism in ordinary cities: Gentrification and temporalities in Turin (1993–2021). Cities. 2023;134:104144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.104144

16. Valiyev A, Wallwork L. Post-Soviet urban renewal and its discontents: gentrification by demolition in Baku. Urban Geography. 2019;40(10):1506–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2019.1627147

17. González Ávila DIN, Garzón Salazar DP, Sánchez Castillo V. Cierre de las empresas del sector turismo en el municipio de Leticia: una caracterización de los factores implicados. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202342. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202342

18. Jackson C. The effect of urban renewal on fragmented social and political engagement in urban environments. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2019;41(4):503–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1478225

19. Mullis D. Urban conditions for the rise of the far right in the global city of Frankfurt: From austerity urbanism, post-democracy and gentrification to regressive collectivity. Urban Studies. 2021;58(1):131–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019878395

20. Rousseau S, Rousseau R. Bibliometric techniques and their use in business and economics research. Journal of Economic Surveys. 2021;35(5):1428–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12415

21. Donthu N, Kumar S, Mukherjee D, Pandey N, Lim WM. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research. 2021;133:285–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

22. Biswas B, Sultana Z, Priovashini C, Ahsan MN, Mallick B. The emergence of residential satisfaction studies in social research: A bibliometric analysis. Habitat International. 2021;109:102336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2021.102336

23. Ledesma F, Malave González BE. Patrones de comunicación científica sobre E-commerce: un estudio bibliométrico en la base de datos Scopus. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):202214. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202214

24. Lam WH, Lam WS, Jaaman SH, Lee PF. Bibliometric Analysis of Information Theoretic Studies. Entropy. 2022;24(10):1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/e24101359

25. Wyly E. The Evolving State of Gentrification. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie. 2019;110(1):12–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12333

26. Borges Machín AY, González Bravo YL. Educación comunitaria para un envejecimiento activo: experiencia en construcción desde el autodesarrollo. Región Científica. 2022;1:202213. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202213

27. Bhavsar NA, Kumar M, Richman L. Defining gentrification for epidemiologic research: A systematic review. Francis JM, editor. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0233361. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233361

28. Finio N. Measurement and Definition of Gentrification in Urban Studies and Planning. Journal of Planning Literature. 2022;37(2):249–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/08854122211051603

29. Preis B, Janakiraman A, Bob A, Steil J. Mapping gentrification and displacement pressure: An exploration of four distinct methodologies. Urban Studies. 2021;58(2):405–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020903011

30. Easton S, Lees L, Hubbard P, Tate N. Measuring and mapping displacement: The problem of quantification in the battle against gentrification. Urban Studies. 2020;57(2):286–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019851953

31. Mujahid MS, Sohn EK, Izenberg J, Gao X, Tulier ME, Lee MM, et al. Gentrification and Displacement in the San Francisco Bay Area: A Comparison of Measurement Approaches. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(12):2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122246

32. Eckerd A, Kim Y, Campbell H. Gentrification and Displacement: Modeling a Complex Urban Process. Housing Policy Debate. 2019;29(2):273–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2018.1512512

33. Delmelle EC. Transit-induced gentrification and displacement: The state of the debate. In: Advances in Transport Policy and Planning. Elsevier; 2021. p. 173–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.atpp.2021.06.005

34. Du T, Zeng N, Huang Y, Vejre H. Relationship between the dynamics of social capital and the dynamics of residential satisfaction under the impact of urban renewal. Cities. 2020;107:102933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102933

35. Mikiewicz P. Social capital and education – An attempt to synthesize conceptualization arising from various theoretical origins. Cogent Education. 2021;8(1):1907956. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1907956

36. Iyanda AE, Lu Y. Perceived Impact of Gentrification on Health and Well-Being: Exploring Social Capital and Coping Strategies in Gentrifying Neighborhoods. The Professional Geographer. 2021;73(4):713–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2021.1924806

37. Bernstein AG, Isaac CA. Gentrification: The role of dialogue in community engagement and social cohesion. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2023;45(4):753–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1877550

38. Levine D, Sussman S, Yavo Ayalon S, Aharon-Gutman M. Rethinking Gentrification and Displacement: Modeling the Demographic Impact of Urban Regeneration. Planning Theory & Practice. 2022;23(4):578–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2022.2117399

39. Hoyos Chavarro YA, Melo Zamudio JC, Sánchez Castillo V. Sistematización de la experiencia de circuito corto de comercialización estudio de caso Tibasosa, Boyacá. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):20228. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc20228

40. Lai Y, Tang B, Chen X, Zheng X. Spatial determinants of land redevelopment in the urban renewal processes in Shenzhen, China. Land Use Policy. 2021;103:105330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105330

41. Tápanes Suárez E, Bosch Nuñez O, Sánchez Suárez Y, Marqués León M, Santos Pérez O. Sistema de indicadores para el control de la sostenibilidad de los centros históricos asociada al transporte. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202352. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202352

42. Wu F. Scripting Indian and Chinese urban spatial transformation: Adding new narratives to gentrification and suburbanisation research. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space. 2020;38(6):980–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420912539

43. Garmany J, Richmond MA. Hygienisation, Gentrification, and Urban Displacement in Brazil. Antipode. 2020;52(1):124–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12584

44. Jover J, Díaz-Parra I. Gentrification, transnational gentrification and touristification in Seville, Spain. Urban Studies. 2020;57(15):3044–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019857585

45. Vázquez Vidal V, Martínez Prats G. Desarrollo regional y su impacto en la sociedad mexicana. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202336. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202336

46. Sax DL, Nesbitt L, Quinton J. Improvement, not displacement: A framework for urban green gentrification research and practice. Environmental Science & Policy. 2022;137:373–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.09.013

47. Bereitschaft B. Gentrification central: A change-based typology of the American urban core, 2000–2015. Applied Geography. 2020;118:102206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102206

48. Pearman FA. Gentrification and Academic Achievement: A Review of Recent Research. Review of Educational Research. 2019;89(1):125–65. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318805924

49. Hu S, Song W, Li C, Lu J. School-gentrifying community in the making in China: Its formation mechanisms and socio-spatial consequences. Habitat International. 2019;93:102045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102045

50. Barton MS, Cohen IFA. How is gentrification associated with changes in the academic performance of neighborhood schools? Social Science Research. 2019;80:230–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.01.005

51. Ellen IG, Horn KM, Reed D. Has falling crime invited gentrification? Journal of Housing Economics. 2019;46:101636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2019.101636

52. Tulier ME, Reid C, Mujahid MS, Allen AM. “Clear action requires clear thinking”: A systematic review of gentrification and health research in the United States. Health & Place. septiembre de 2019;59:102173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102173

53. Díaz-Parra I. Generating a critical dialogue on gentrification in Latin America. Progress in Human Geography. 2021;45(3):472–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520926572

54. Guatemala Mariano A, Martínez Prats G. Capacidades tecnológicas en empresas sociales emergentes: una ruta de impacto social. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):2023111. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2023111

55. López-Morales E, Ruiz-Tagle J, Santos Junior OA, Blanco J, Salinas Arreortúa L. State-led gentrification in three Latin American cities. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2023;45(8):1397–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1939040

56. Lorenzen M. Rural gentrification, touristification, and displacement: Analysing evidence from Mexico. Journal of Rural Studies. 2021;86:62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.05.015

57. Sanabria Martínez MJ. Construir nuevos espacios sostenibles respetando la diversidad cultural desde el nivel local. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):20222. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc20222

58. Navarrete Escobedo D. Foreigners as gentrifiers and tourists in a Mexican historic district. Urban Studies. 2020;57(15):3151–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019896532

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Rogelio Jiménez Zapata.

Data curation: Rogelio Jiménez Zapata.

Formal analysis: Rogelio Jiménez Zapata.

Drafting - original draft: Rogelio Jiménez Zapata.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Rogelio Jiménez Zapata.