doi: 10.62486/gen202454

ORIGINAL

The gentrification of health: an analysis of its convergence

La gentrificación de la salud: un análisis de su convergencia

Ana María Chaves Cano1 ![]() *

*

1Fundación Universitaria Juan N. Corpas. Bogotá, Colombia.

Cite as: Chaves Cano AM. The gentrification of health: an analysis of its convergence. Gentrification. 2024; 2:54. https://doi.org/10.62486/gen202454

Submitted: 19-06-2023 Revised: 20-09-2023 Accepted: 04-01-2024 Published: 05-01-2024

Editor: Estela

Hernández-Runque ![]()

ABSTRACT

The article explores how gentrification impacts public health, with a particular focus on urban transformations and their repercussions on communities. Using a desk review methodology in the Scopus database, this study analyses the literature between 2018 and 2023 to identify how changes in urban structure influence the accessibility and quality of health services. It highlights that while gentrification can improve infrastructure and services, it can also exacerbate health inequalities and lead to the displacement of vulnerable populations. The analysis reveals the need to adapt medical education to these new urban challenges and suggests future lines of research to develop more equitable interventions. This multidisciplinary approach offers valuable insights for more inclusive policies that consider both urban development and health equity.

Keywords: Gentrification; Public Health; Health Inequalities; Medical Education; Health Policies.

RESUMEN

El artículo explora cómo la gentrificación impacta en la salud pública, con un enfoque particular en las transformaciones urbanas y sus repercusiones en las comunidades. Utilizando una metodología de revisión documental en la base de datos Scopus, este estudio analiza la literatura entre 2018 y 2023 para identificar cómo los cambios en la estructura urbana influyen en la accesibilidad y la calidad de los servicios de salud. Se destaca que, mientras la gentrificación puede mejorar la infraestructura y los servicios, también puede exacerbar las desigualdades de salud y provocar el desplazamiento de poblaciones vulnerables. El análisis revela la necesidad de adaptar la educación médica a estos nuevos desafíos urbanos y sugiere futuras líneas de investigación para desarrollar intervenciones más equitativas. Este enfoque multidisciplinario ofrece perspectivas valiosas para políticas más inclusivas que consideren tanto el desarrollo urbano como la equidad en salud.

Palabras clave: Gentrificación; Salud Pública; Desigualdades de Salud; Educación Médica; Políticas de Salud.

INTRODUCTION

The health sector faces multifaceted challenges that are both complex and urgent, demanding a continual reassessment of current strategies and practices.(1,2,3,4) Chief among these challenges are inequity in access to health services, the growing burden of chronic disease, and the changing dynamics of urban populations.(5,6,7,8) This article delves into how gentrification, a predominantly urban phenomenon, intervenes and can potentially reshape the public health landscape.

Gentrification is generally understood as the process by which previously low-income or deteriorating neighbourhoods undergo significant transformation, attracting more affluent residents and resulting in improved local infrastructure and services, including healthcare.(9,10,11,12) However, this process raises critical questions about equity and inclusion, especially regarding who benefits from these improvements.(13,14,15,16)

Historically, gentrification has been studied primarily for its impact on the real estate market and social dynamics. However, its relationship to health is a relatively new and emerging field.(17,18,19) Researchers and public health policymakers have begun to recognize that changes in the urban fabric due to gentrification can have profound implications for public health, from improved access to new and improved health services to the potential displacement of vulnerable populations who may face even greater barriers to accessing health care.(20,21,22,23)

This analysis is based on a detailed documentary review of the existing literature extracted from the Scopus database covering 2018 to 2023. Through this approach, we seek to understand how urban interventions associated with gentrification are reshaping access to health and identify the transformations needed within the health sector to respond effectively to these new challenges.(24,25)

The health sector must adapt and transform to address the direct effects of gentrification and anticipate the changing needs of evolving urban populations.(26,27,28) This implies reconsidering how health services are designed, located and managed in urban areas.(29,30,31) In addition, public health plans must consider how gentrification affects different groups within cities, especially those who might be displaced or marginalized during this process.(32,33,34,35)

The review also seeks to establish a critical dialogue on current policies and practices in public health, urging greater inclusion of socioeconomic and cultural perspectives in urban planning and health policy.(36,37) This study aims to identify the consequences of gentrification on health and propose ways for health systems to anticipate and mitigate adverse effects, ensuring that the benefits of renewed urban infrastructures are accessible to all. By addressing these issues, the article positions itself at the forefront of efforts to ensure that public health and urban planning go hand in hand in creating healthy and equitable environments for future generations.

METHOD

The methodology employed was based on a documentary review with an interpretive approach. The study was designed to explore how gentrification impacts health in different contexts, especially in urban areas undergoing socioeconomic transformation.

Studies were selected through a systematic search of the Scopus database, limiting the publication of articles between 2018 and 2023. Keywords related to “gentrification” and “health” were used, and the filters were adjusted to include only those papers that addressed both topics explicitly. The final selection of studies was made after assessing the relevance of the title and abstract, ensuring that each contributed significantly to understanding the topic in question.

Phases of the thematic analysis

Initial coding: The selected texts were read in detail, and open coding was performed to identify key concepts.

Code grouping: Similar codes were grouped into broader thematic categories that reflected emerging patterns in the data.

Review and definition of themes: Categories were reviewed to ensure internal consistency, and the final themes that would structure the study findings were defined.

Interpretation: Themes were interpreted in the context of existing literature on gentrification and health, seeking to provide an in-depth understanding of how these phenomena are intertwined.

Ethical Principles Considered

Fundamental ethical principles were respected, including confidentiality and anonymity of secondary sources. In addition, appropriate citations of all documents and studies were made to support the claims and analyses presented in the article.

Limitations of the Study

A notable limitation was the small sample of studies that met the specific inclusion criteria, which could affect the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the very nature of the documentary review precluded making strong causal claims due to reliance on previous publications that could be biased toward specific contexts or methodologies.

This methodology allowed for a detailed and contextualized understanding of the effects of gentrification on health; while acknowledging the limitations, it suggests the need for broader future research to validate and expand on the preliminary findings.

RESULTS

After conducting a qualitative literature review on gentrification and health between 2018 and 2023 in the Scopus database, five main trends were identified:

The dual impact of gentrification on health: It was observed that gentrification could improve neighbourhood conditions, such as reduced crime and increased property values.(38,39,40,41) However, it can also foster negative conditions associated with worse health outcomes, such as disruption of social networks due to residential displacement and increases in stress.(42,43,44)

Effects of green gentrification: Green gentrification, driven by green urbanization initiatives, has shown potential benefits and drawbacks for residents’ health. While some residents may benefit from improved access to green space, marginalized residents often experience a diminished sense of community and belonging.(45,46,47,48,49)

Health inequalities due to gentrification: Studies have found that gentrification can have differential health effects among different social groups. Marginalized groups tend to suffer more from the negative effects of gentrification, underscoring the importance of considering the social dimensions of urban interventions.(50,51)

Change in social and physical environments: Gentrification frequently leads to changes in neighbourhoods’ social and physical environment, affecting residents’ health and well-being.(52) These changes include alterations in eating patterns, physical activity, drug and alcohol use, and healthcare-seeking behaviours.(53)

Residents’ perceptions of gentrification: Differences in perceptions of gentrification among residents are also a notable trend.(54,55) Some see the changes as positive, while others feel they threaten their quality of life and well-being, impacting their mental and physical health.(56)

The state of the art in the study of gentrification and its impact on health has developed significantly in recent years, reflecting a growing academic and policy interest in the intersections between urban change and public health. The literature on this topic spans diverse disciplines, including public health, urban sociology, and spatial planning, which has enriched the understanding of how urban transformation affects communities.

Initially, studies on gentrification focused on understanding the economic and social dynamics that drive neighbourhood transformation.(57) Early research identified gentrification as an urban phenomenon linked primarily to improved infrastructure and increased real estate values.(58) However, attention soon shifted to the consequences these urban changes have on the original residents, especially in terms of displacement and access to essential services.

Regarding health, the initial focus was on physical improvements that could lead to a healthier environment, such as increased green space, improved health services and reduced pollution.(59,60) However, more recent studies have documented mixed effects. On the one hand, some research indicated that gentrification can lead to improved quality of life and access to health services. On the other hand, other studies have highlighted increased stress, anxiety and other mental health problems related to displacement and housing insecurity.

The literature has also explored how gentrification affects different social groups unequally. Studies have shown that while some residents benefit from urban improvements, vulnerable groups, especially those with less economic power or less robust social networks, face significant risks of deteriorating health. This has led to a call for more inclusive policies that balance urban development with protecting the rights and health of pre-existing residents.

Finally, a critical need for more empirical research has been identified to unravel the specific mechanisms through which gentrification affects health. This includes longitudinal studies that can follow residents over time to understand better the long-term impacts of living in neighbourhoods experiencing gentrification. In summary, the current state of the art reflects a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the health impacts of gentrification, highlighting both potential benefits and significant risks and underscoring the need for more integrative research and public policy approaches that are cognizant of the social complexities involved in this phenomenon (figure 1).

Figure 1. Most frequent terms

Integrative analysis

Triangulating the trends identified in the review on gentrification and health with findings from previous studies allows for a richer and more nuanced understanding of the topic. Below, we expand on these results by integrating findings from other relevant research.

Previous studies have also documented mixed effects of gentrification on community health. For example, some have noted improvements in local infrastructure and services that could enhance public health. In contrast, others highlight increased stress and anxiety among displaced residents due to uncertainty and loss of community.

Research on green gentrification has indicated that while these initiatives may increase aesthetic value and accessibility to green space, they often result in socioeconomic and cultural exclusion of long-term residents. This phenomenon has been observed in multiple studies discussing how new green developments can alienate pre-existing residents who feel a diminished sense of belonging.

The literature consistently highlights that gentrification can exacerbate existing health inequalities. The negative effects of gentrification, such as housing insecurity and reduced access to essential services, tend to disproportionately affect vulnerable groups, reinforcing the need for more equitable intervention approaches.

Changes in social and physical environments due to gentrification directly affect residents’ mental and physical health. Studies have documented how the transformation of neighbourhoods can lead to changes in health behaviours, including physical activity and diets, as well as increases in stress and social alienation.

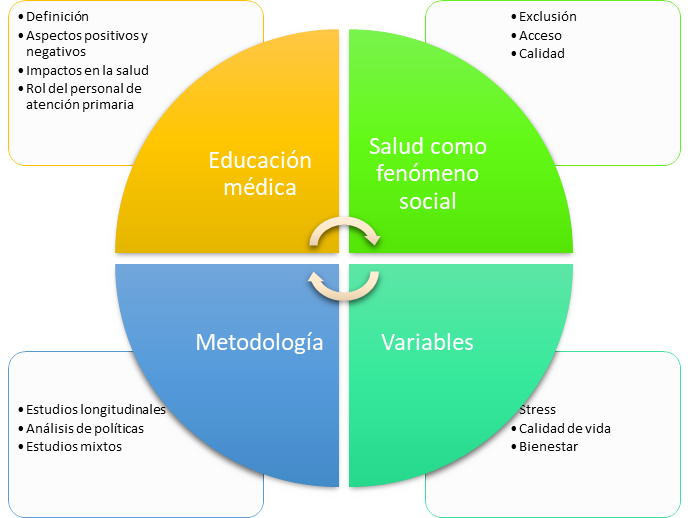

Perceptions of gentrification vary significantly among residents, directly influencing their psychological well-being. Some studies have found that while some residents may perceive gentrification as improving their quality of life, others may experience a sense of loss and rootlessness, which can have profound implications for their mental health (figure 2).

Figure 2. Gentrification analysis matrix in the context of health care

DISCUSSION

The discussion of health gentrification in the Latin American context, based on the findings of the qualitative review conducted, revealed several significant challenges and opportunities for future research. The studies reviewed highlighted how gentrification-driven changes affect not only the physical structure of neighbourhoods but also the health of their inhabitants. In Latin America, the challenges are particularly acute due to marked social and economic inequalities, exacerbated by gentrification processes often not accompanied by adequate protective policies for low-income residents.

One of the challenges identified was the need to transform medical education to address these new urban contexts. Gentrification brings demographic changes that demand a review of how medicine is taught, especially about the emerging health needs and disparities associated with these urban changes. Therefore, medical education in Latin America needs to adapt and train health professionals who understand and can act effectively in these transformed environments.

In addition, the discussion underscored the importance of developing lines of research that deepen the understanding of how gentrification influences public health. Future research could explore the long-term impact of gentrification on mental and physical health, investigate the specific effects of gentrification on different demographic groups, and evaluate interventions that could mitigate the negative effects of gentrification. It was also recommended that further public policies be studied to promote more equitable gentrification, including improvements in access to health services and quality of life for pre-existing residents without forcing them to move.

In summary, while gentrification can offer opportunities to revitalize urban areas and improve access to services, it also presents significant challenges that must be addressed through medical education and future research to ensure that all residents, especially those in vulnerable situations, benefit equitably from these changes.

CONCLUSIONS

Gentrification was confirmed to have a dual impact on health in the regions studied. While gentrification improved infrastructure and health services in some cases, in others, it exacerbated inequalities and increased stress and insecurity among displaced residents. This phenomenon highlighted the need for more inclusive policies addressing urban development and health equity.

A gap was identified in adapting medical education in the face of the challenges imposed by gentrification. The training of future health professionals needs to incorporate a deeper understanding of the social determinants of health, especially those related to rapid urban change and its effects on vulnerable communities.

The need for more longitudinal studies exploring the long-term effects of gentrification on health, especially in Latin American contexts, was highlighted. Future research should focus on designing and evaluating interventions that can mitigate the negative impacts of gentrification and promote a more equitable redistribution of health resources.

Ultimately, the article underscored the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to understanding and addressing the public health consequences of gentrification. It advocated for greater collaboration among urban planners, health professionals, and policymakers to ensure that urban revitalisation benefits are distributed fairly among all affected populations.

REFERENCES

1. Oleribe OE, Momoh J, Uzochukwu BS, Mbofana F, Adebiyi A, Barbera T, et al. Identifying Key Challenges Facing Healthcare Systems In Africa And Potential Solutions. International Journal of General Medicine. 2019;Volume 12:395–403. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S223882

2. Valladolid Benavides AM, Neyra Cornejo FI, Hernández Hernández O, Callupe Cueva PC, Akintui Antich JP. Adicción a redes sociales en estudiantes de una universidad nacional de Junín (Perú). Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202323. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202353

3. Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Medicine. 2018;16(95). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1089-4

4. Khan Y, O’Sullivan T, Brown A, Tracey S, Gibson J, Généreux M, et al. Public health emergency preparedness: a framework to promote resilience. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2018;18(1344). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6250-7

5. Lazar M, Davenport L. Barriers to Health Care Access for Low Income Families: A Review of Literature. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2018;35(1):28–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370016.2018.1404832

6. Hajat C, Stein E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: A narrative review. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2018;12:284–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.008

7. Connolly C, Keil R, Ali SH. Extended urbanisation and the spatialities of infectious disease: Demographic change, infrastructure and governance. Urban Studies [Internet]. 2021;58(2):245–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020910873

8. Guatemala Mariano A, Martínez Prats G. Capacidades tecnológicas en empresas sociales emergentes: una ruta de impacto social. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):2023111. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2023111

9. Wyly E. The Evolving State of Gentrification. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie. 2019;110(1):12–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12333

10. Smith GS, Breakstone H, Dean LT, Thorpe RJ. Impacts of Gentrification on Health in the US: a Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Urban Health. 2020;97(6):845–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-020-00448-4

11. Tulier ME, Reid C, Mujahid MS, Allen AM. “Clear action requires clear thinking”: A systematic review of gentrification and health research in the United States. Health & Place. 2019;59:102173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102173

12. Estrada Herrera P, Pueblita Mares J. Metodología de construcción esbelta en la optimización de los resultados de un proyecto de edificación. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):2023113. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2023113

13. Cole HVS, Anguelovski I, Triguero-Mas M, Mehdipanah R, Arcaya M. Promoting Health Equity Through Preventing or Mitigating the Effects of Gentrification: A Theoretical and Methodological Guide. Annual Review of Public Health. 2023;44(1):193–211. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-071521-113810

14. Bernstein AG, Isaac CA. Gentrification: The role of dialogue in community engagement and social cohesion. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2023;45(4):753–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1877550

15. Bhavsar NA, Kumar M, Richman L. Defining gentrification for epidemiologic research: A systematic review. Francis JM, editor. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0233361. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233361

16. Murgas Téllez B, Henao-Pérez AA, Guzmán Acuña L. Oposición pública o manifestación social frente a proyectos de inversión en Chile y Colombia. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):2023112. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2023112

17. Arkaraprasertkul N. Gentrification and its contentment: An anthropological perspective on housing, heritage and urban social change in Shanghai. Urban Studies. 2018;55(7):1561–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016684313

18. Izenberg JM, Mujahid MS, Yen IH. Health in changing neighborhoods: A study of the relationship between gentrification and self-rated health in the state of California. Health & Place. 2018;52:188–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.06.002

19. Cole HVS. A call to engage: considering the role of gentrification in public health research. Cities & Health. 2020;4(3):278–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2020.1760075

20. Triguero-Mas M, Anguelovski I, García-Lamarca M, Argüelles L, Perez-del-Pulgar C, Shokry G, et al. Natural outdoor environments’ health effects in gentrifying neighborhoods: Disruptive green landscapes for underprivileged neighborhood residents. Social Science & Medicine. 2021;279:113964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113964

21. Schnake-Mahl AS, Jahn JL, Subramanian SV, Waters MC, Arcaya M. Gentrification, Neighborhood Change, and Population Health: a Systematic Review. Journal of Urban Health. 2020;97:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00400-1

22. Pérez Egües MA, Torres Zerquera LDC, Hernández Delgado M. Evaluación de las condiciones del Gabinete Psicopedagógico de la Universidad de Cienfuegos en la gestión de servicios de orientación virtual. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):202384. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202384

23. Kim H, Woosnam KM, Kim H. Urban gentrification, social vulnerability, and environmental (in) justice: Perspectives from gentrifying metropolitan cities in Korea. Cities. 2022;122:103514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103514

24. Cole HVS, Mehdipanah R, Gullón P, Triguero-Mas M. Breaking Down and Building Up: Gentrification, Its drivers, and Urban Health Inequality. Current Environmental Health Reports. 2021;8:157–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-021-00309-5

25. Delong S. Urban health inequality in shifting environment: systematic review on the impact of gentrification on residents’ health. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023;11:1154515. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1154515/full

26. Silva JP, Santos CJ, Torres E, Martínez-Manrique L, Barros H, Ribeiro AI. A double-edged sword: Residents’ views on the health consequences of gentrification in Porto, Portugal. Social Science & Medicine. 2023;336:116259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116259

27. Hyra D, Moulden D, Weted C, Fullilove M. A Method for Making the Just City: Housing, Gentrification, and Health. Housing Policy Debate. 2019;29(3):421–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2018.1529695

28. Turenne CP, Gautier L, Degroote S, Guillard E, Chabrol F, Ridde V. Conceptual analysis of health systems resilience: A scoping review. Social Science & Medicine. 2019;232:168–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.020

29. Patrício L, Sangiorgi D, Mahr D, Čaić M, Kalantari S, Sundar S. Leveraging service design for healthcare transformation: toward people-centered, integrated, and technology-enabled healthcare systems. Journal of Service Management. 2020;31(5):889–909. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-11-2019-0332

30. Schiavone F, Leone D, Sorrentino A, Scaletti A. Re-designing the service experience in the value co-creation process: an exploratory study of a healthcare network. Business Process Management Journal. 2020;26(4):889–908. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-11-2019-0475/full/html

31. Ruiz Díaz De Salvioni VV. Estrategias innovadoras para un aprendizaje continuo y efectivo durante emergencias sanitarias en Ciudad del Este. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202338. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202338

32. Anguelovski I, Triguero-Mas M, Connolly JJ, Kotsila P, Shokry G, Pérez Del Pulgar C, et al. Gentrification and health in two global cities: a call to identify impacts for socially-vulnerable residents. Cities & Health. 2020;4(1):40–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2019.1636507

33. López‐Gay A, Cocola‐Gant A, Russo AP. Urban tourism and population change: Gentrification in the age of mobilities. Population Space and Place. 2021;27(1):e2380. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2380

34. Agbai CO. Shifting neighborhoods, shifting health: A longitudinal analysis of gentrification and health in Los Angeles County. Social Science Research. 2021;100:102603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102603

35. Bhavsar NA, Yang LZ, Phelan M, Shepherd-Banigan M, Goldstein BA, Peskoe S, et al. Association between Gentrification and Health and Healthcare Utilization. Journal of Urban Health. 2022;99(6):984–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-022-00692-w

36. Ramirez-Rubio O, Daher C, Fanjul G, Gascon M, Mueller N, Pajín L, et al. Urban health: an example of a “health in all policies” approach in the context of SDGs implementation. Globalization and Health. 2019;15(1):87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-019-0529-z

37. Tápanes Suárez E, Bosch Nuñez O, Sánchez Suárez Y, Marqués León M, Santos Pérez O. Sistema de indicadores para el control de la sostenibilidad de los centros históricos asociada al transporte. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202352. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202352

38. Almeida R, Patrício P, Brandão M, Torres R. Can economic development policy trigger gentrification? Assessing and anatomising the mechanisms of state-led gentrification. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. 2022;54(1):84–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211050076

39. Ellen IG, Horn KM, Reed D. Has falling crime invited gentrification? Journal of Housing Economics. 2019;46:101636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2019.101636

40. Candipan J, Riley AR, Easley JA. While Some Things Change, Do Others Stay the Same? The Heterogeneity of Neighborhood Health Returns to Gentrification. Housing Policy Debate. 2023;33(1):129–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2022.2076715

41. Bockarjova M, Botzen WJW, Van Schie MH, Koetse MJ. Property price effects of green interventions in cities: A meta-analysis and implications for gentrification. Environmental Science & Policy. 2020;112:293–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.024

42. Rubin CL, Chomitz VR, Woo C, Li G, Koch-Weser S, Levine P. Arts, Culture, and Creativity as a Strategy for Countering the Negative Social Impacts of Immigration Stress and Gentrification. Health Promotion Practice. 2021;22(1_suppl):131S-140S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839921996336

43. Vázquez Vidal V, Martínez Prats G. Desarrollo regional y su impacto en la sociedad mexicana. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202336. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202336

44. Tran LD, Rice TH, Ong PM, Banerjee S, Liou J, Ponce NA. Impact of gentrification on adult mental health. Health Services Research. 2020;55(3):432–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13264

45. Eckerd A, Kim Y, Campbell H. Gentrification and Displacement: Modeling a Complex Urban Process. Housing Policy Debate. 2019;29(2):273–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2018.1512512

46. Mujahid MS, Sohn EK, Izenberg J, Gao X, Tulier ME, Lee MM, et al. Gentrification and Displacement in the San Francisco Bay Area: A Comparison of Measurement Approaches. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(12):2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122246

47. Jelks NO, Jennings V, Rigolon A. Green Gentrification and Health: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(3):907. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030907

48. Sax DL, Nesbitt L, Quinton J. Improvement, not displacement: A framework for urban green gentrification research and practice. Environmental Science & Policy. 2022;137:373–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.09.013

49. Sanabria Martínez MJ. Construir nuevos espacios sostenibles respetando la diversidad cultural desde el nivel local. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):20222. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc20222

50. Anguelovski I, Cole HVS, O’Neill E, Baró F, Kotsila P, Sekulova F, et al. Gentrification pathways and their health impacts on historically marginalized residents in Europe and North America: Global qualitative evidence from 14 cities. Health & Place. 2021;72:102698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102698

51. Versey HS. Gentrification, Health, and Intermediate Pathways: How Distinct Inequality Mechanisms Impact Health Disparities. Housing Policy Debate. 2023;33(1):6–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2022.2123249

52. Rigolon A, Németh J. Toward a socioecological model of gentrification: How people, place, and policy shape neighborhood change. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2019;41(7):887–909. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1562846

53. Cole HVS, Anguelovski I, Connolly JJT, García-Lamarca M, Perez-del-Pulgar C, Shokry G, et al. Adapting the environmental risk transition theory for urban health inequities: An observational study examining complex environmental riskscapes in seven neighborhoods in Global North cities. Social Science & Medicine. 2021;277:113907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113907

54. Antunes B, March H, Connolly JJT. Spatializing gentrification in situ: A critical cartography of resident perceptions of neighbourhood change in Vallcarca, Barcelona. Cities [Internet]. 2020 [citado el 30 de agosto de 2024];97:102521. https://doi.org/

55. Youngbloom AJ, Thierry B, Fuller D, Kestens Y, Winters M, Hirsch JA, et al. Gentrification, perceptions of neighborhood change, and mental health in Montréal, Québec. SSM - Population Health. 2023;22:101406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101406

56. Atuesta LH, Hewings GJD. Housing appreciation patterns in low-income neighborhoods: Exploring gentrification in Chicago. Journal of Housing Economics. 2019;44:35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2018.08.005

57. Verlaan T, Hochstenbach C. Gentrification through the ages: A long-term perspective on urban displacement, social transformation and resistance. City. 2022;26(2–3):439–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2022.2058820

58. Finio N. Measurement and Definition of Gentrification in Urban Studies and Planning. Journal of Planning Literature. 2022;37(2):249–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/08854122211051603

59. Cole HVS, Triguero-Mas M, Connolly JJT, Anguelovski I. Determining the health benefits of green space: Does gentrification matter? Health & Place. 2019;57:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.02.001

60. González Vallejo R. La transversalidad del medioambiente: facetas y conceptos teóricos. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):202393. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202393

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Ana María Chaves Cano.

Data curation: Ana María Chaves Cano.

Research: Ana María Chaves Cano.

Methodology: Ana María Chaves Cano.

Project administration: Ana María Chaves Cano.

Writing - original draft: Ana María Chaves Cano.

Writing - revision and editing: Ana María Chaves Cano.