doi: 10.62486/gen202467

REVIEW

Displacement as a social problem and its relationship to gentrification

El desplazamiento como problema social y su relación con la gentrificación

Javier Gonzalez-Argote1

![]() *, Emanuel Jose Maldonado2

*, Emanuel Jose Maldonado2

![]() *

*

1Universidad Abierta Interamericana, Facultad de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

2AG Editor. Montevideo, Uruguay.

Cite as: Gonzalez-Argote J, Maldonado EJ. Displacement as a social problem and its relationship to gentrification. Gentrification. 2024; 2:67. https://doi.org/10.62486/gen202467

Submitted: 08-07-2023 Revised: 07-12-2023 Accepted: 09-04-2024 Published: 10-04-2024

Corresponding author: Javier Gonzalez-Argote *

ABSTRACT

The article examines the impact of gentrification on the social fabric and urban structure of cities between 2018 and 2023. This study focuses on how neighborhood renovation can lead to the displacement of vulnerable communities, addressing a critical issue in contemporary urban planning. Through a methodological approach that combines bibliometric analysis and integrative synthesis, the dynamics of change in urban neighborhoods and their consequences for long-term residents are investigated. The article highlights the need to thoroughly understand the economic, social, and cultural dimensions of gentrification to mitigate its adverse effects and promote more inclusive development practices. By situating displacement within the context of broader urban strategies, this work seeks to offer balanced perspectives on revitalization policies and their impacts on local communities.

Keywords: Gentrification; Social Displacement; Urban Renewal; Bibliometric Analysis; Urban Planning.

RESUMEN

El artículo examina el impacto de la gentrificación en el tejido social y la estructura urbana de las ciudades entre 2018 y 2023. Este estudio se centra en cómo la renovación de barrios puede llevar al desplazamiento de comunidades vulnerables, al abordar un tema crítico en la planificación urbana contemporánea. A través de un enfoque metodológico que combina análisis bibliométrico y síntesis integrativa, se investigan las dinámicas de cambio en los barrios urbanos y sus consecuencias para los residentes de larga duración. El artículo destaca la necesidad de comprender a fondo las dimensiones económicas, sociales y culturales de la gentrificación para mitigar sus efectos adversos y promover prácticas de desarrollo más inclusivas. Al situar el desplazamiento en el contexto de estrategias urbanas más amplias, este trabajo busca ofrecer perspectivas equilibradas sobre las políticas de revitalización y sus impactos en las comunidades locales.

Palabras clave: Gentrificación; Desplazamiento Social; Renovación Urbana; Análisis Bibliométrico; Planificación Urbana.

INTRODUCTION

Gentrification, a complex and multifaceted process, is a central theme in contemporary urban studies, reflecting profound socioeconomic and cultural transformations in cities worldwide. This phenomenon, which involves the renewal and revaluation of hitherto marginalized or declining urban neighborhoods, brings opportunities for urban revitalization and significant challenges, including the displacement of vulnerable populations.(1,2,3)

Historically, gentrification is studied from diverse perspectives spanning economics, sociology, and urban geography; it offers a rich body of literature suggesting both positive and negative effects. However, this study seeks to move beyond the traditional 'urban upgrading' narrative to focus on the human consequences of the phenomenon, specifically the displacement of long-term residents and the erosion of established communities.(4,5,6)

By transforming the face of urban neighborhoods, gentrification alters the physical appearance of cities and modifies the social and cultural dynamics embedded in those communities. This process can generate tensions between the new residents with greater purchasing power and the original inhabitants, affecting the neighborhood's social cohesion and identity.(7,8,9)

In addition, gentrification is often accompanied by increased housing prices and services, which can result in the exclusion of those who cannot afford the rising costs, thus exacerbating socioeconomic inequalities in cities. On the other hand, gentrification can also have positive effects, such as improved urban infrastructure, job creation, and increased safety in renewed areas. However, it is critical to critically analyze who benefits and who is harmed by these changes to ensure that urban policies are equitable and sustainable in the long run.(10,11,12)

This article seeks to explore the intrinsic dynamics between gentrification and its effects on the social fabric of urban communities. It focuses on the period between 2018 and 2023, a particularly relevant interval given the rapid change in urban policies and real estate investment patterns in multiple geographic contexts. Through a methodology that combines bibliometric analysis and integrative synthesis, this paper aims to identify emerging patterns, measure impacts, and discuss possible strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of gentrification.

METHOD

A methodology that integrated bibliometric analysis and integrative synthesis was developed to address the study of gentrification and its relationship with displacement as a social problem. This approach allowed us to examine the evolution of research in the field comprehensively and the synthesis of relevant findings to better understand this complex interaction between gentrification and displacement.(13,14,15)

Stage 1: Bibliographic Review and Source Selection

We began with a comprehensive review of the academic literature on gentrification and social displacement, focusing on papers published between 2018 and 2023. Articles were selected from recognized academic databases, ensuring a broad representation of theoretical and empirical perspectives. Inclusion criteria for the studies encompassed thematic relevance, methodological rigor, and geographic diversity, emphasizing Latin American contexts.

Stage 2: Bibliometric Analysis

Bibliometric analysis tools were used to identify trends, main authors, and the most influential publications in gentrification and displacement. This analysis allowed us to map the structure of the field of study and to understand the evolution of the academic debate on the topic. Indicators used included frequency of publications, citations per article, and inter-institutional collaborations.

Stage 3: Integrative Synthesis

An integrative synthesis was conducted to extract key findings from the selected studies, integrating results from different research to form a holistic understanding of how gentrification affects social displacement. This stage included categorizing studies according to their methodological approaches, results, and recommendations.

Stage 4: Qualitative Analysis

A qualitative analysis of the data collected was conducted to explore the dimensions and indicators of the gentrification phenomenon and its impact on displacement. The dimensions considered included changes in neighborhood demographics, changes in housing prices, modifications in local infrastructure, and alterations in the socioeconomic and cultural composition of affected communities. Specific indicators measured were displacement rates, real estate price indices, and statistics on changes in the ethnic and income composition of the neighborhoods studied.

Stage 5: Preparation of Conclusions and Recommendations

Finally, the findings were synthesized to formulate conclusions about the observed patterns of gentrification and displacement. Based on the results, recommendations were developed for policymakers, urban planners, and affected communities to mitigate the adverse effects of gentrification and promote more inclusive and sustainable urban development practices.

RESULTS

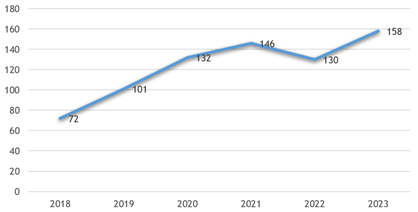

Analysis of the bibliometric data shows a gradual increase in the number of publications over the years (figure 1). In 2018, 72 publications were recorded, followed by 101 in 2019, 132 in 2020, 146 in 2021, 130 in 2022, and 158 in 2023. This increase suggests a growing interest and academic attention to this topic during the period analyzed.

Figure 1. Publications by year

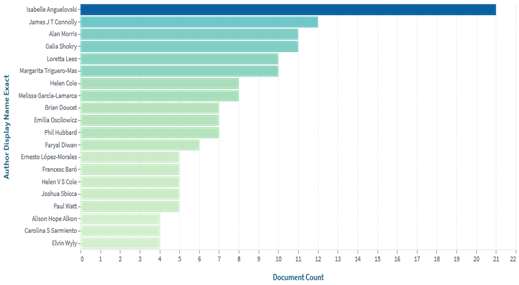

Notable authors include Anguelovski, Connolly, Morris, and Shokry, whose contributions are significant in studying displacement and gentrification (figure 2). Their research enriches the field and provides fundamental perspectives for understanding the complexities of this social issue.

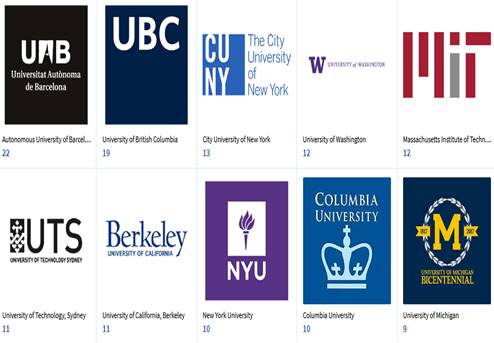

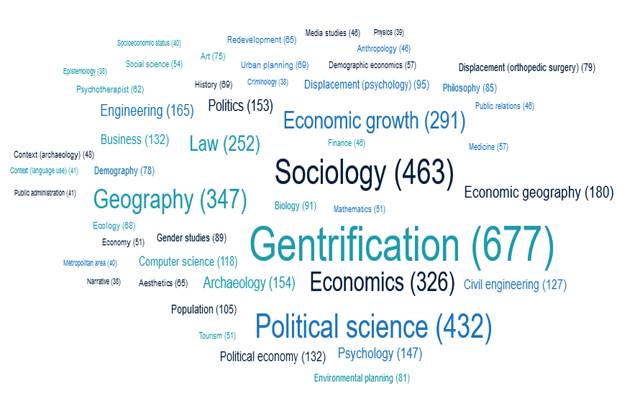

The most involved in research on this issue are the Autonomous University of Barcelona, the University of British Columbia, and the City University of New York (figure 3). These institutions play a crucial role in generating knowledge and research on displacement and gentrification, contributing to advancing the academic field. The fields most researched about displacement and gentrification include gentrification, sociology, political science, geography, and economics (figure 4). These interdisciplinary fields offer diverse and enriching perspectives to address the complexities of this urban phenomenon.(16)

Figure 2. Leading authors in the subject area

Figure 3. Institutions most involved in the thematic area

Figure 4. Fields of study

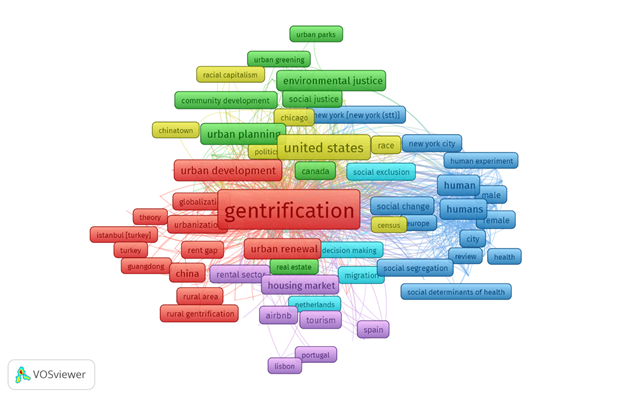

The most prominent keywords from the research include terms fundamental to understanding this urban phenomenon. Among the most relevant keywords are “gentrification,” “urban renewal,” “social change,” “urban development,” and “urban planning” (figure 5). These keywords encapsulate the core concepts addressed in the academic literature on gentrification and displacement and provide a solid foundation for exploring and understanding the urban and social dynamics involved in these processes. The interplay between these key terms reflects the complexity of contemporary urban changes and their implications on affected communities.

Analyzing academic publications that use these keywords reveals a multidimensional approach encompassing theoretical, methodological, and practical aspects of gentrification and displacement. These keywords act as fundamental pillars underpinning research in this field, facilitating the identification of emerging trends, debates, and perspectives that enrich the academic discourse on these critical urban issues.(17)

In addition, the analysis of these texts identifies five key trends in the evolution of gentrification and displacement research during the period studied. These trends focus on definitions and conceptualizations, transatlantic comparative methodologies, the importance of gentrification indicators and measurement variables, the impact of tourism and green gentrification, and critical and resistance perspectives. These bibliometric data reveal a dynamic and multifaceted landscape in the study of displacement and gentrification, highlighting the importance of approaching this issue from multiple perspectives and approaches to understand its social, economic, and urban implications comprehensively.(18)

Figure 5. Keyword Co-occurrence

There is a tendency to debate and clarify the definition of gentrification, differentiating it from related concepts such as displacement and urban renewal. Studies focus on how gentrification is conceptualized in different contexts, addressing the need for a more precise and relational definition to understand and measure the phenomenon better.(19,20)

Some research adopts comparative approaches, especially between regions such as Spain and Mexico, to understand how gentrification is adapted and applied in different urban contexts. These studies highlight the differences and similarities in the reception and application of the term and its political and social implications in different urban settings.(21,22,23)

There is interest in developing and refining indicators to measure gentrification more effectively. Studies explore various sociodemographic and housing variables, such as age, ethnicity, income, and housing characteristics, to construct more robust indices that reflect the phenomenon's complexity.(24,25)

A growing interest is identified in studying the relationship between gentrification and tourism and the emerging concept of green gentrification. These approaches consider how the transformation of urban areas into tourist destinations or green zones can influence the dynamics of gentrification, affecting local communities in specific ways.(26,27)

Finally, research incorporates critical perspectives that examine responses and forms of resistance to gentrification. Studies analyze how affected communities respond to gentrification processes and their strategies to mitigate its effects, highlighting the importance of participatory and community-based approaches to urban planning.(28,29)

These trends reflect a diversification in the methodologies and approaches used to study gentrification and displacement. They underscore the need for a more nuanced and contextualized approach to understanding and addressing this complex urban phenomenon.(30,31)

Integrative synthesis

After conducting a documentary review that combined bibliometric analysis with a qualitative integrative synthesis focused on 2018-2023, five main trends are identified in gentrification and its relationship to displacement as a social problem. These trends offer a deep insight into how gentrification impacts urban communities and their displacement dynamics.

Reconfiguration of urban space

The reconfiguration of urban space driven by gentrification goes beyond a mere revitalization process. This transformation involves the creation of new urban landscapes that reflect physical changes, such as the construction of modern housing and attractive commercial spaces and a profound social and cultural reorganization. The arrival of residents with greater purchasing power alters these neighborhoods' social and economic dynamics, generating tensions and conflicts around the identity and belonging of the original inhabitants.(32,33)

Moreover, gentrification affects current residents and the history and collective memory of a place. The expulsion of original inhabitants to peripheral areas leads to the loss of community connections that have been ingrained for generations, which can result in the disappearance of local traditions and mutual support networks. Likewise, the challenge of adapting to unfamiliar environments on the periphery, with limited access to essential services and job opportunities, deepens inequalities and marginalization of these displaced groups.(34,35)

In this sense, the reconfiguration of urban space through gentrification raises fundamental questions about equity, inclusion, and social justice in the development of modern cities. It is crucial to address these urban transformation processes holistically, considering the physical and economic aspects and the social and cultural impacts that influence the quality of life and well-being of all urban communities.(36,37)

Impact on local communities

The impact of gentrification on local communities goes beyond the simple geographic relocation of residents. This process entails profound transformations in these neighborhoods' social and cultural structures. The dispersion of the original inhabitants leads to the dissolution of community ties and social cohesion. These fundamental elements have underpinned these communities' identity and daily life over time.(38,39)

The loss of these social ties and bonds of belonging can generate an emotional and cultural void in displaced communities. The disappearance of traditional meeting places, the fragmentation of support networks, and the alteration of interpersonal dynamics can weaken the quality of life and emotional well-being of those forced to leave their homes.(40,41)

Resilience and adaptation

In response to gentrification, certain communities exhibit resistance and adaptation, seeking to counteract its impacts through social activism or the implementation of specific public policies. Despite this, these attempts often face significant challenges and present marked disparities, as their effectiveness is closely linked to each community's organizational capacity and resources.(42,43)

Community resistance manifests through social movements, collective actions, and local organizations that seek to protect the interests and rights of residents affected by gentrification. These initiatives may include protests, awareness campaigns, negotiations with local authorities, or promoting fair and affordable housing alternatives. On the other hand, adaptation implies the ability to adjust to the changes imposed by gentrification, whether through the creation of mutual support networks, the diversification of economic activities, or the preservation of cultural identity in new urban contexts.(44,45)

Role of urban and economic policies

Housing and urban planning policies play a key role in shaping gentrification processes, as they can significantly influence the dynamics of real estate markets and the spatial distribution of the population. In many cases, these policies are designed to encourage real estate investment and urban development, often resulting in the acceleration of gentrification and the displacement of local communities.(46,47)

The orientation of urban and economic policies toward attracting investors and economic growth can negatively affect the most vulnerable communities, as they prioritize profitability and real estate market expansion over the affordable housing needs and welfare of low-income residents. This approach can lead to the expulsion of the original inhabitants of gentrified neighborhoods.(48,49)

Long-term socioeconomic effects

Gentrification-induced displacement not only has immediate consequences on affected communities but also generates significant long-term impacts on the socioeconomic structure of cities. Displaced residents often face persistent challenges that affect their quality of life and economic prospects in their new environments, which can lead to increasingly entrenched cycles of poverty and segregation.(50,51)

One of the long-term socioeconomic effects of gentrifying displacement is increased living costs for displaced residents. Forced to move to peripheral or less developed areas, these individuals may struggle and need help accessing affordable housing, quality basic services, and equitable job opportunities. This situation can result in greater economic and social precariousness, exacerbating inequalities and exclusion in the urban fabric.(52,53)

DISCUSSION

In reviewing the trends identified in the documentary research on gentrification and displacement and in the bibliometric trends of studies on the subject, similarities and differences were observed that reflect the evolution of the academic approach and its practical applications, especially in Latin American contexts. These observations offer a more complete view of how the region approaches and understands the phenomenon.

In terms of similarities, both sets of trends highlight the importance of a deep and contextualized understanding of gentrification, which focuses on the physical transformation of urban spaces and the socio-cultural and economic changes it entails. The need for clear definitions and the application of rigorous methodologies to measure and analyze the phenomenon were common aspects in both areas of study.(54,55)

However, the differences between these two approaches were also evident. While documentary research focused on the direct and often detrimental effects of gentrification, such as displacement and loss of cultural identity of communities, bibliometric trends showed a growing interest in developing comparative and multidimensional methods to study these processes. This latter approach includes exploring more diversified variables and integrating concepts such as green gentrification and touristification, which link gentrification to broader debates on sustainable development and urban change.(56,57)

In Latin America, the challenges are particularly acute due to the region's unique and often volatile urban dynamics. Latin American cities face a complex interplay of economic, political, and social factors that are exacerbated by urban development policies that often favor higher-income sectors, leaving vulnerable populations at risk of exclusion and displacement. This situation is exacerbated by inefficient governance mechanisms that can mediate urban conflicts and provide equitable solutions.(58,59)

Therefore, academic discussion and research on gentrification and displacement must continue to evolve to address these issues in a way that recognizes the particularities of each context and promotes more inclusive and sustainable development in Latin American cities. As highlighted in the bibliometric trends, integrating multidisciplinary and comparative approaches could offer new perspectives and solutions to these persistent challenges.

CONCLUSIONS

Documentary research and bibliometric analysis on gentrification and displacement reveal the complexity and evolution of academic and practical approaches to this urban phenomenon. The need for a deep and contextualized understanding of gentrification, which considers its physical effects on the urban environment and its socio-cultural and economic repercussions, becomes fundamental to designing effective and equitable interventions. The differences between documentary and bibliometric research trends highlight the diversity of perspectives and approaches in the study of gentrification and displacement. While some studies focus on the direct negative impacts of gentrification, others explore comparative and multidimensional approaches to understand these processes in different urban contexts better. In the case of Latin America, where urban dynamics present particular challenges, it is crucial to address gentrification, consider local realities, and promote inclusive strategies that protect vulnerable populations from exclusion and displacement. Integrating multidisciplinary and comparative approaches can open new perspectives and contribute to more equitable and sustainable development in the region's cities.

REFERENCES

1. Borges Machín AY, González Bravo YL. Educación comunitaria para un envejecimiento activo: experiencia en construcción desde el autodesarrollo. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):202212. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202213

2. Schnake-Mahl A, Jahn J, Subramanian S, Waters M, Arcaya M. Gentrification, Neighborhood Change, and Population Health: a Systematic Review. Journal of Urban Health. 2020;97:1-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00400-1

3. Gibbons J, Barton M, Reling T. Do gentrifying neighbourhoods have less community? Evidence from Philadelphia. Urban Studies. 2020;57:1143-1163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019829331

4. Cole H, Mehdipanah R, Gullón P, Triguero-Mas M. Breaking Down and Building Up: Gentrification, Its drivers, and Urban Health Inequality. Current Environmental Health Reports. 2021;8:157-166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-021-00309-5

5. Debortoli DO, Brignole NB. Inteligencia empresarial para estimular el giro comercial en el microcentro de una ciudad de tamaño intermedio. Región Científica. 2024;3(1):2024195. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2024195

6. Rigolon A, Nemeth J. Toward a socioecological model of gentrification: How people, place, and policy shape neighborhood change. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2019;41:887-909. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1562846

7. Smith G, Breakstone H, Dean L, Thorpe R. Impacts of Gentrification on Health in the US: a Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Urban Health. 2020;97:845-856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-020-00448-4

8. Versey H, Murad S, Willems P, Sanni M. Beyond Housing: Perceptions of Indirect Displacement, Displacement Risk, and Aging Precarity as Challenges to Aging in Place in Gentrifying Cities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234633

9. González Ávila DIN, Garzón Salazar DP, Sánchez Castillo V. Cierre de las empresas del sector turismo en el municipio de Leticia: una caracterización de los factores implicados. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202342. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202342

10. Sun D. Urban health inequality in shifting environment: systematic review on the impact of gentrification on residents’ health. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1154515

11. Mendoza-Graf A, Collins R, Dastidar M, Beckman R, Hunter G, Troxel W, Dubowitz T. Changes in psychosocial wellbeing over a five-year period in two predominantly Black Pittsburgh neighbourhoods: A comparison between gentrifying and non-gentrifying census tracts. Urban Studies. 2023;60:1139-1157. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980221135385

12. Halasz J. Between gentrification and supergentrification: Hybrid processes of socio-spatial upscaling. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2021;45:771-796. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1877551

13. Eslava-Zapata R, Mogollón Calderón OZ, Chacón Guerrero E. Socialización organizacional en las universidades: estudio empírico. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):202369. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202369

14. Eslava-Zapata R, Gómez-Cano C, Chacón-Guerrero E, Esteban-Montilla R. Análisis Bibliométrico sobre estilos de liderazgo: contribuciones y tendencia de la investigación. Educación y Sociedad. 2023;15(6):574-87 https://rus.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/rus/article/view/4175

15. Easton S, Lees L, Hubbard P, Tate N. Measuring and mapping displacement: The problem of quantification in the battle against gentrification. Urban Studies. 2020;57:286-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019851953

16. Ledesma F, Malave-González BE. Patrones de comunicación científica sobre E-commerce: un estudio bibliométrico en la base de datos Scopus. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):202214. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202214

17. Elliott-Cooper, A., Hubbard, P., & Lees, L. Moving beyond Marcuse: Gentrification, displacement and the violence of un-homing. Progress in Human Geography. 2019;44:492-509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519830511

18. González Vallejo R. La transversalidad del medioambiente: facetas y conceptos teóricos. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):202393. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202393

19. Lukens, D. Configurations of gentrification and displacement: chronic displacement as an effect of redevelopment in Seoul, South Korea. Urban Geography. 2020;42:812-832. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1742467

20. Gómez-Cano C, Sánchez-Castillo V, Clavijo-Gallego TA. Mapping the Landscape of Netnographic Research: A Bibliometric Study of Social Interactions and Digital Culture. Data and Metadata. 2023;2(25). https://doi.org/10.56294/dm202325

21. Jover, J., & Díaz-Parra, I. Gentrification, transnational gentrification and touristification in Seville, Spain. Urban Studies. 2020;57:3044-3059. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019857585

22. Escobedo, D. Foreigners as gentrifiers and tourists in a Mexican historic district. Urban Studies. 2020;57:3151-3168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019896532

23. López-Morales, E., Ruiz-Tagle, J., Junior, O., Blanco, J., & Arreortúa, L. State-led gentrification in three Latin American cities. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2021;45:1397-1417. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1939040

24. Moreira AdJ, Reis Fonseca RM. La inserción de los movimientos sociales en la protección del medio ambiente: cuerpos y aprendizajes en el Recôncavo da Bahia. Región Científica. 2024;3(1):2024208. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2024208

25. Rigolon, A., & Collins, T. The green gentrification cycle. Urban Studies. 2022;60:770-785. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980221114952

26. Sánchez-Ledesma, E., Vásquez-Vera, H., Sagarra, N., Peralta, A., Porthé, V., & Díez, È. Perceived pathways between tourism gentrification and health: A participatory Photovoice study in the Gòtic neighborhood in Barcelona. Social science & medicine. 2022; 258, 113095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113095

27. riguero-Mas, M., Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J., Martin, N., Matheney, A., Cole, H., Pérez-Del-Pulgar, C., García-Lamarca, M., Shokry, G., Argüelles, L., Conesa, D., Gallez, E., Sarzo, B., Beltrán, M., Máñez, J., Martínez-Minaya, J., Oscilowicz, E., Arcaya, M., & Baró, F. Exploring green gentrification in 28 global North cities: the role of urban parks and other types of greenspaces. Environmental Research Letters. 2022;17. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac9325

28. Rodríguez-Torres E, Davila-Cisneros JD, Gómez-Cano C. La formación para la configuración de proyectos de vida: una experiencia mediante situaciones de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Varona. 2024;79(e2391) http://revistas.ucpejv.edu.cu/index.php/rVar/article/view/2391

29. Blok, A. Urban green gentrification in an unequal world of climate change. Urban Studies. 2020;57:2803-2816. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019891050

30. Mujahid, M., Sohn, E., Izenberg, J., Gao, X., Tulier, M., Lee, M., & Yen, I. Gentrification and Displacement in the San Francisco Bay Area: A Comparison of Measurement Approaches. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122246

31. Higuera Carrillo EL. Aspectos clave en agroproyectos con enfoque comercial: Una aproximación desde las concepciones epistemológicas sobre el problema rural agrario en Colombia. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):20224. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc20224

32. Sigler, T., & Wachsmuth, D. New directions in transnational gentrification: Tourism-led, state-led and lifestyle-led urban transformations. Urban Studies. 2020; 57, 3190 - 3201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020944041

33. Silva, C., Giannotti, M., & Almeida, C. Dynamic modeling to support an integrated analysis among land use change, accessibility and gentrification. Land Use Policy. 2020;99:104992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104992

34. Jelks, N., Jennings, V., & Rigolon, A. Green Gentrification and Health: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030907

35. Carvalho, L., Chamusca, P., Fernandes, J., & Pinto, J. Gentrification in Porto: floating city users and internationally-driven urban change. Urban Geography. 2019;40:565-572. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2019.1585139

36. Thurber, A., Krings, A., Martinez, L., & Ohmer, M. Resisting gentrification: The theoretical and practice contributions of social work. Journal of Social Work. 2019;21:26-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017319861500

37. Noroña González Y, Colala Troya AL, Peñate Hernández JI. La orientación para la proyección individual y social en la educación de jóvenes y adultos: un estudio mixto sobre los proyectos de vida. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):202389. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202389

38. Pérez Gamboa AJ, García Acevedo Y, García Batán J. Proyecto de vida y proceso formativo universitario: un estudio exploratorio en la Universidad de Camagüey. Trasnsformación. 2019;15(3):280-96 http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2077-29552019000300280

39. Bletscher C, Spiers S. “Step by Step We Were Okay Now”: An Exploration of the Impact of Social Connectedness on the Well-Being of Congolese and Iraqi Refugee Women Resettled in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023;20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075324

40. Verduyn P, Schulte-Strathaus J, Kross E, Hülsheger U. When do smartphones displace face-to-face interactions and what to do about it? Computers in Human Behavior. 2020;114:106550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106550

41. Matthews V, Longman J, Bennett-Levy J, Braddon M, Passey M, Bailie R, Berry H. Belonging and Inclusivity Make a Resilient Future for All: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Post-Flood Social Capital in a Diverse Australian Rural Community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207676

42. Quinn T, Adger W, Butler C, Walker-Springett K. Community Resilience and Well-Being: An Exploration of Relationality and Belonging after Disasters. Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 2020;111:577-590. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1782167

43. Sutton S. Gentrification and the Increasing Significance of Racial Transition in New York City 1970–2010. Urban Affairs Review. 2020;56:65-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087418771224

44. Gómez-Cano C, Sánchez-Castillo V. Evaluación del nivel de madurez en la gestión de proyectos de una empresa prestadora de servicios públicos. Económicas CUC. 2021;42(2):133-44. https://doi.org/10.17981/econcuc.42.2.2021.Org.7

45. Versey H. Gentrification, Health, and Intermediate Pathways: How Distinct Inequality Mechanisms Impact Health Disparities. Housing Policy Debate. 2022;33:6-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2022.2123249

46. Sanabria Martínez MJ. Construir nuevos espacios sostenibles respetando la diversidad cultural desde el nivel local. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):20222. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc20222

47. Mösgen A, Rosol M, Schipper S. State-led gentrification in previously ‘un-gentrifiable’ areas: Examples from Vancouver/Canada and Frankfurt/Germany. European Urban and Regional Studies. 2019;26:419-433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776418763010

48. Wissoker P. Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities. Journal of Urban Technology. 2022;29:166-168. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2021.2018165

49. Thorpe A. Regulatory gentrification: Documents, displacement and the loss of low-income housing. Urban Studies. 2020;58:2623-2639. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020960569

50. Hwang J, Ding L. Unequal Displacement: Gentrification, Racial Stratification, and Residential Destinations in Philadelphia. American Journal of Sociology. 2020;126:354-406. https://doi.org/10.1086/711015

51. Santos, C., Paciência, I., & Ribeiro, A. Neighbourhood Socioeconomic Processes and Dynamics and Healthy Ageing: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116745

52. Hoover, D. The Injustice of Gentrification. Political Theory. 2023;51:925-954. https://doi.org/10.1177/00905917231178295

53. Verlaan, T., & Hochstenbach, C. Gentrification through the ages. City. 2022;26:439-449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2022.2058820

54. Rucks-Ahidiana, Z. Racial composition and trajectories of gentrification in the United States. Urban Studies. 2020;58:2721-2741. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020963853

55. Tulumello, S., & Allegretti, G. Articulating urban change in Southern Europe: Gentrification, touristification and financialisation in Mouraria, Lisbon. European Urban and Regional Studies. 2020;28:111-132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776420963381

56. Rucks-Ahidiana, Z. Theorizing Gentrification as a Process of Racial Capitalism. City & Community. 2021;21:173-192. https://doi.org/10.1177/15356841211054790

57. Yañez-Pagans, P., Martínez, D., Mitnik, O., Scholl, L., & Vázquez, A. Urban transport systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: lessons and challenges. Latin American Economic Review. 2019;28:1-25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40503-019-0079-z

58. Verbavatz, V., & Barthelemy, M. Modeling the spatial dynamics of income in cities. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science. 2023;51:128-139. https://doi.org/10.1177/23998083231171397

59. Comaru, F., & Westphal, M. Housing, Urban Development and Health in Latin America: Contrasts, Inequalities and Challenges. Reviews on Environmental Health. 2021;19(3-4):329-346. https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh-2004-19-3-410

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.

Data curation: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.

Formal analysis: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.

Research: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.

Methodology: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.

Project Management: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.

Resources: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.

Software: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.

Supervision: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.

Validation: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.

Visualization: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.

Writing - original draft: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Javier Gonzalez-Argote, Emanuel Jose Maldonado.