doi: 10.62486/gen202469

REVIEW

Mental Health and Its Relationship with the Gentrification Process

La salud mental y su relación con el proceso de gentrificación

Ariadna Gabriela Matos Matos1 ![]() *

*

1Universidad de Camagüey, Departamento de Psicología-Sociología. Camagüey, Cuba.

Cite as: Matos Matos AG. Mental Health and Its Relationship with the Gentrification Process. Gentrification. 2024; 2:69. https://doi.org/10.62486/gen202469

Submitted: 09-07-2023 Revised: 12-12-2023 Accepted: 11-04-2024 Published: 12-04-2024

Editor: Estela

Hernández-Runque ![]()

Corresponding author: Ariadna Gabriela Matos Matos *

ABSTRACT

The article addresses the complex interaction between urban transformation and the psychological well-being of affected residents. Through a comprehensive literature review of publications between 2010 and 2023, this study synthesizes existing evidence on how gentrification influences the incidence of mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, and stress. The analysis reveals that urban changes not only alter the physical infrastructure of neighborhoods but also displace communities, disrupt social support networks, and exacerbate mental health problems among vulnerable populations. This work highlights the importance of incorporating mental health considerations into urban planning and policies to mitigate the negative impacts of gentrification and promote the development of sustainable and psychologically healthy communities.

Keywords: Gentrification; Mental Health; Anxiety; Urban Planning; Mental Disorders.

RESUMEN

El artículo aborda la compleja interacción entre la transformación urbana y el bienestar psicológico de los residentes afectados. A través de una revisión documental exhaustiva de literatura publicada entre 2010 y 2023, este estudio sintetiza las evidencias existentes sobre cómo la gentrificación influye en la incidencia de trastornos mentales como la ansiedad, la depresión y el estrés. El análisis revela que los cambios urbanos no solo modifican la infraestructura física de los barrios, sino que también desplazan comunidades, rompen redes de apoyo social y exacerban problemas de salud mental entre las poblaciones vulnerables. Este trabajo destaca la importancia de incorporar consideraciones de salud mental en la planificación y políticas urbanas para mitigar los impactos negativos de la gentrificación y promover el desarrollo de comunidades sostenibles y psicológicamente saludables.

Palabras clave: Gentrificación; Salud Mental; Ansiedad; Planificación Urbana; Trastornos Mentales.

INTRODUCTION

The relationship between gentrification and mental health is a critical area of study that has gained prominence in recent decades. As cities worldwide face rapid and often disruptive urban transformations, gentrification becomes a more latent issue.(1,2,3)

Historically, gentrification is understood primarily through its economic and physical impacts, such as rising real estate values and the transformation of neighborhoods. However, the narrative is shifting towards a more holistic understanding that includes the psychosocial consequences of gentrification. This shift in focus is crucial, given that the restructuring of urban spaces alters geographies and displaces communities by affecting the social continuity and personal identity of its inhabitants.(4,5,6,7)

The traditional narrative on gentrification has evolved into a broader perspective that recognizes the social and psychological implications of urban transformation processes. This shift in focus is critical, as the reorganization of urban spaces modifies the physical environment and impacts community relationships.(8,9,10)

This article explores how changes in the urban fabric influence the psychological well-being of people affected by these processes. This research provides a framework better to understand the intersections between urban development and mental health, underscores the need for urban policies that seek economic benefit and the psychological well-being of affected communities, and provides a framework better to understand the intersections between urban development and mental health.

METHODS

The methodology employed in this study consisted of a detailed documentary review to explore the relationship between gentrification and mental health. Scholarly articles, research reports, and case studies published between 2013 and 2023 in Scopus, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar were selected and reviewed.(11,12,13)

· Paper Selection: inclusion criteria were applied to select studies that directly addressed the effects of gentrification on mental health. Papers that provided empirical data, theoretical analysis, or critical reviews on the topic were prioritized.

· Data Extraction: from each selected source, data related to the psychological impacts of gentrification were extracted, including types of associated mental disorders, risk factors, and affected populations. In addition, information was collected on intervention strategies and policy recommendations suggested by the authors.

· Content Analysis: a qualitative content analysis was conducted to synthesize and compare the main findings of the reviewed documents. This analysis enabled the identification of common patterns, discrepancies, and gaps in the existing literature.

This desk review approach provided a solid foundation for understanding how urban restructuring through gentrification impacts the mental health of affected communities. This, in turn, shaped the discussions and conclusions of the study.(14,15,16)

RESULTS

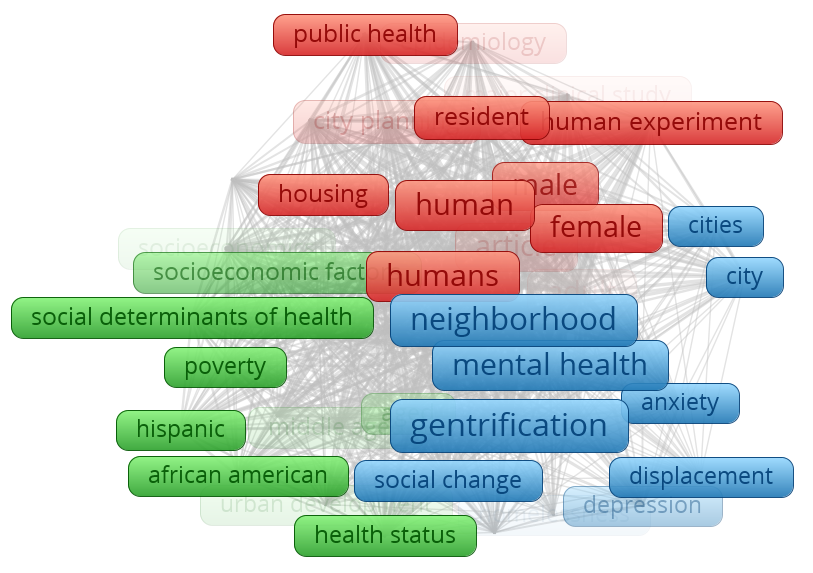

Following a review of current trends in research on the relationship between gentrification and mental health, three main trends are identified. These trends highlight the importance of considering the psychosocial impacts of gentrification on the mental health of affected communities (figure 1).

Visualization of the word cloud reveals a complex web of interconnected concepts revolving around mental health and gentrification. Terms such as “mental health,” “urban renewal,” “neighborhood,” “housing,” “neighborhood,” “social problems,” and “socioeconomics” suggest an intricate web of ideas influenced by multiple factors. By closely analyzing the key terms in the cloud, one can identify trends that define the relationship between gentrification and mental health.

The prominent presence of concepts such as “mental health” and “neighborhood” coincides with the increase in mental health problems in communities affected by gentrification. Likewise, including terms such as “social problems” and “displacement” reflects the deterioration of cohesion among inhabitants due to these urban transformation processes. On the other hand, the appearance of terms such as “socioeconomics,” “displacement,” and “social change” in the word cloud suggests the existence of disparities in access to resources in gentrified contexts, aligning with the third identified trend.

Figure 1. Current trends in research on the relationship between gentrification and mental health

Increase in Mental Health Problems

Gentrification, by causing an increase in mental health problems such as anxiety and depression, poses several significant challenges, especially for those individuals who are displaced from their long-established homes and communities. Detailed studies have shown that hospitalization rates for mental disorders are notably higher among those affected by gentrification, suggesting a profound impact on the emotional and psychological stability of these individuals.(17,18)

One of the most troubling aspects of this phenomenon is the loss of social connections and support that results from forced displacement. This loss can have devastating long-term mental health consequences. The rupture with community and support networks can lead to feelings of isolation, alienation, and loss of identity, which contributes to the onset or aggravation of mental disorders.(19)

It is essential to address not only the physical and economic aspects of gentrification but also the psychosocial impacts that can have detrimental and long-lasting effects on the mental health of those affected. Implementing psychological support programs, promoting the creation of meeting spaces, and strengthening community support networks are key measures to mitigate the negative effects on mental health caused by gentrification.(20,21)

In addition, it is critical to raise community and decision-makers awareness of the importance of considering the psychosocial impacts of gentrification on the mental health of affected individuals. Adopting holistic and people-centered approaches is crucial to address this complex and multifaceted problem effectively.(22,23)

Deterioration of Community Cohesion

Gentrification, by triggering drastic changes in the structure of communities, not only impacts individual mental health but can also undermine community cohesion as a whole. The forced displacement of residents and the transformation of the social and cultural environment can lead to the loss of collective identity, fragmentation of support networks, and diminished solidarity among neighbors.(24,25)

The lack of strong social ties and a sense of belonging can exacerbate the isolation and alienation experienced by those displaced. The loss of the community support network may leave people without emotional resources to cope with the emotional and psychological challenges that arise during gentrification, which in turn may contribute to a generalized deterioration of mental health in the affected community.(26,27,28)

In addition, the disintegration of community cohesion can hinder people's ability to advocate for their collective needs, making it difficult to organize collective responses and seek solutions in the face of the negative impacts of gentrification. It is, therefore, essential to recognize and address these effects on mental health and social cohesion as an integral part of any urban planning strategy that promotes healthy and sustainable communities in urban change.(29,30)

Inequalities in Access to Resources

Gentrification, by raising living costs in affected areas, often creates additional barriers for low-income residents in their access to essential resources, including mental health services. More expensive housing and services in these areas can result in the expulsion of vulnerable populations, leaving them without access to the care and support needed to maintain adequate mental health.(31,32,33)

This exclusion from critical services can deepen existing disparities in access to mental health care. Which creates an even greater gap between those who can afford to access treatment and therapy and those who cannot.(34,35)

In addition, gentrified areas tend to prioritize services and resources that align with the needs and preferences of more affluent new residents, leaving displaced communities with fewer options and opportunities for mental health support. This lack of equitable access to mental health services can intensify socioeconomic and mental health inequities.(36,37)

To address this issue comprehensively, it is crucial to implement policies that ensure equitable access to mental health services for all population segments, regardless of socioeconomic status. This includes the creation of affordable and culturally sensitive mental health programs, as well as the promotion of diversity and inclusion in mental health care services.(38,39)

In addition, specific support mechanisms should be established for displaced communities to ensure that they have access to the resources necessary to preserve their emotional and psychological well-being amidst the changes brought about by gentrification. Collaboration between government entities, community-based organizations, and mental health service providers is critical to address these inequities in access to resources and ensure an equitable approach to mental health service provision in areas affected by gentrification.(40,41)

DISCUSSION

In discussing the role of psychology professionals in gentrification contexts, it was noted that they played key roles in mitigating the adverse effects of this phenomenon on the mental health of affected populations. The research showed that gentrification not only led to physical displacement but also significant psychological disorders, such as stress, anxiety, and depression, especially among the most vulnerable populations.

Psychologists, in this context, worked closely with communities to offer emotional and psychotherapeutic support, helping individuals deal with the trauma of displacement and loss of community. Group therapy was an effective tool for fostering community resilience; it allowed residents to share experiences and coping strategies in a supportive environment.(42,43,44)

In addition, psychology professionals played a crucial role in researching and evaluating the mental health impacts of gentrification. They provided critical data that informed public policy and urban interventions through longitudinal studies and community assessments. Their work helped illustrate the need to consider the consequences of gentrification beyond economic benefits, focusing on its human and social costs.(45,36,47)

In sum, psychologists provided clinical services and acted as advocates for affected communities by working toward more inclusive and ethical policies that recognized and addressed the multifaceted realities of displacement and its effects on mental health. Their work focused on individual care and advocating for structural changes that would comprehensively address the psychosocial challenges resulting from gentrification.(48,49,50)

CONCLUSIONS

Gentrification has a direct and significant impact on the mental health of individuals affected by displacement. The studies reviewed demonstrate an increase in the prevalence of disorders such as anxiety and depression among displaced populations, underscoring the need to address the psychosocial consequences of urban restructuring in development policies.

Gentrification leads to the breakdown of community cohesion, resulting in a significant loss of social support networks for the original residents. This community disintegration is a key factor contributing to the deterioration of mental health and highlights the importance of preserving and strengthening social structures in urban planning processes.

Urban interventions must integrate mental health considerations. Policies and planning should include strategies that minimize the negative impact of gentrification on vulnerable communities, such as providing accessible mental health services and encouraging initiatives that promote inclusion and psychological well-being for all citizens.

REFERENCES

1. Thurber, A., Krings, A., Martinez, L., Ohmer, M. Resisting gentrification: The theoretical and practice contributions of social work. Journal of Social Work. 2019;21:26-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017319861500

2. Easton, S., Lees, L., Hubbard, P., Tate, N. Measuring and mapping displacement: The problem of quantification in the battle against gentrification. Urban Studies. 2020;57:286-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019851953

3. Santos, C., Paciência, I., Ribeiro, A. Neighbourhood Socioeconomic Processes and Dynamics and Healthy Ageing: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116745

4. Borges Machín AY, González Bravo YL. Educación comunitaria para un envejecimiento activo: experiencia en construcción desde el autodesarrollo. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):202212. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202213

5. Blok, A. Urban green gentrification in an unequal world of climate change. Urban Studies. 2020;57:2803-2816. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019891050

6. Comaru, F., Westphal, M. Housing, Urban Development and Health in Latin America: Contrasts, Inequalities and Challenges. Reviews on environmental health. 2021;19(3-4):329-346. https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh-2004-19-3-410

7. Holt, S., Río-González, A., Massie, J., Bowleg, L. “I Live in This Neighborhood Too, Though”: the Psychosocial Effects of Gentrification on Low-Income Black Men Living in Washington, D.C.. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2020;8:1139-1152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00870-z

8. González Vallejo R. La transversalidad del medioambiente: facetas y conceptos teóricos. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):202393. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202393

9. Heath, S., Rabinovich, A., Barreto, M. Exploring the social dynamics of urban regeneration: A qualitative analysis of community members’ experiences. The British Journal of Social Psychology. 2022;62:521-539. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12578

10. Manley, A., Silk, M. Remembering the City: Changing Conceptions of Community in Urban China. City & Community. 2019;18:1240-1266. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12466

11. Alroy, K., Cavalier, H., Crossa, A., Wang, S., Liu, S., Norman, C., Sanderson, M., Gould, L., Lim, S. Can changing neighborhoods influence mental health? An ecological analysis of gentrification and neighborhood-level serious psychological distress—New York City, 2002–2015. PLOS ONE. 2023;18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0283191

12. Zayas-Costa, M., Cole, H., Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J., Bartoll, X., Triguero-Mas, M. Mental Health Outcomes in Barcelona: The Interplay between Gentrification and Greenspace. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179314

13. Debortoli DO, Brignole NB. Inteligencia empresarial para estimular el giro comercial en el microcentro de una ciudad de tamaño intermedio. Región Científica. 2024;3(1):2024195. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2024195

14. Wood B, Cubbin C, Hernandez E, DiNitto D, Vohra-Gupta S, Baiden P, Mueller E. The Price of Growing Up in a Low-Income Neighborhood: A Scoping Review of Associated Depressive Symptoms and Other Mood Disorders among Children and Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023;20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196884

15. Barton M, Weil F, Voorde N. Interrogating the Importance of Collective Resources for the Relationship of Gentrification With Health. Housing Policy Debate. 2022;33:30-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2022.2055616

16. Fong P, Cruwys T, Haslam C, Haslam S. Neighbourhood identification buffers the effects of (de-)gentrification and personal socioeconomic position on mental health. Health & Place. 2019;57:247-256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.05.013

17. Rodríguez-Torres E, Davila-Cisneros JD, Gómez-Cano C. La formación para la configuración de proyectos de vida: una experiencia mediante situaciones de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Varona. 2024;79(e2391) http://revistas.ucpejv.edu.cu/index.php/rVar/article/view/2391

18. Smith G, Breakstone H, Dean L, Thorpe R. Impacts of Gentrification on Health in the US: a Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Urban Health. 2020;97:845-856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-020-00448-4

19. Pérez Gamboa AJ, García Acevedo Y, García Batán J. Proyecto de vida y proceso formativo universitario: un estudio exploratorio en la Universidad de Camagüey. Trasnsformación. 2019;15(3):280-96 http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2077-29552019000300280

20. Sun D. Urban health inequality in shifting environment: systematic review on the impact of gentrification on residents’ health. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.115451

21. Higuera Carrillo EL. Aspectos clave en agroproyectos con enfoque comercial: Una aproximación desde las concepciones epistemológicas sobre el problema rural agrario en Colombia. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):20224. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc20224

22. Sadler R, Felton J, Rabinowitz J, Powell T, Latimore A, Tandon D. Inequitable Housing Practices and Youth Internalizing Symptoms: Mediation Via Perceptions of Neighborhood Cohesion. Urban Planning. 2022;7:153-166. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v7i4.5410

23. Jelks N, Jennings V, Rigolon A. Green Gentrification and Health: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030907

24. Bhavsar N, Kumar M, Richman L. Defining gentrification for epidemiologic research: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2020;15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233361

25. Versey H, Murad S, Willems P, Sanni M. Beyond Housing: Perceptions of Indirect Displacement, Displacement Risk, and Aging Precarity as Challenges to Aging in Place in Gentrifying Cities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234633

26. Mendoza-Graf A, Collins R, Dastidar M, Beckman R, Hunter G, Troxel W, Dubowitz T. Changes in psychosocial wellbeing over a five-year period in two predominantly Black Pittsburgh neighbourhoods: A comparison between gentrifying and non-gentrifying census tracts. Urban Studies. 2023;60:1139-1157. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980221135385

27. Linares Giraldo M, Rozo Carvajal KJ, Sáenz López JT. Impacto de la pandemia en el comportamiento del comercio B2C en Colombia. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202320. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202320

28. Versey, H. Gentrification, Health, and Intermediate Pathways: How Distinct Inequality Mechanisms Impact Health Disparities. Housing Policy Debate. 2022;33:6-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2022.2123249

29. Sutton, S. Gentrification and the Increasing Significance of Racial Transition in New York City 1970–2010. Urban Affairs Review. 2020;56:65-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087418771224

30. Gibbons, J., Barton, M., Reling, T. Do gentrifying neighbourhoods have less community? Evidence from Philadelphia. Urban Studies. 2020;57:1143-1163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019829331

31. Halasz, J. Between gentrification and supergentrification: Hybrid processes of socio-spatial upscaling. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2021;45:771-796. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1877551

32. López-Gónzalez YY. Competencia digital del profesorado para las habilidades TIC en el siglo XXI: una evaluación de su desarrollo. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):2023119. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2023119

33. Schnake-Mahl, A., Jahn, J., Subramanian, S., Waters, M., Arcaya, M. Gentrification, Neighborhood Change, and Population Health: a Systematic Review. Journal of Urban Health. 2020;97:1-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00400-1

34. Rigolon, A., Nemeth, J. Toward a socioecological model of gentrification: How people, place, and policy shape neighborhood change. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2019;41:887-909. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1562846

35. Eslava-Zapata R, Mogollón Calderón OZ, Chacón Guerrero E. Socialización organizacional en las universidades: estudio empírico. Región Científica. 2023;2(2):202369. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202369

36. Verbavatz, V., Barthelemy, M. Modeling the spatial dynamics of income in cities. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science. 2023;51:128-139. https://doi.org/10.1177/23998083231171397

37. Gómez-Cano C, Sánchez-Castillo V. Systematic review on Augmented Reality in health education. Gamification and Augmented Reality. 2023;1:28. https://doi.org/10.56294/gr202328

38. Arundell, L., Greenwood, H., Baldwin, H., Kotas, E., Smith, S., Trojanowska, K., Cooper, C. Advancing mental health equality: a mapping review of interventions, economic evaluations and barriers and facilitators. Systematic Reviews. 2020;9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01333-6

39. Hailemariam, M., Fekadu, A., Medhin, G., Prince, M., Hanlon, C. Equitable access to mental healthcare integrated in primary care for people with severe mental disorders in rural Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2019;13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0332-5

40. García-Goñi, M., Stoyanova, A., Nuño-Solínis, R. Mental Illness Inequalities by Multimorbidity, Use of Health Resources and Socio-Economic Status in an Aging Society. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020458

41. González Ávila DIN, Garzón Salazar DP, Sánchez Castillo V. Cierre de las empresas del sector turismo en el municipio de Leticia: una caracterización de los factores implicados. Región Científica. 2023;2(1):202342. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc202342

42. Gómez-Cano C, Sánchez-Castillo V. Evaluación del nivel de madurez en la gestión de proyectos de una empresa prestadora de servicios públicos. Económicas CUC. 2021;42(2):133-44. https://doi.org/10.17981/econcuc.42.2.2021.Org.7

43. Verlaan, T., Hochstenbach, C. Gentrification through the ages. City. 2022;26:439-449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2022.2058820

44. Cole, H., Mehdipanah, R., Gullón, P., Triguero-Mas, M. Breaking Down and Building Up: Gentrification, Its drivers, and Urban Health Inequality. Current Environmental Health Reports. 2021;8:157-166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-021-00309-5

45. Moreira AdJ, Reis Fonseca RM. La inserción de los movimientos sociales en la protección del medio ambiente: cuerpos y aprendizajes en el Recôncavo da Bahia. Región Científica. 2024;3(1):2024208. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc2024208

46. Gómez-Cano C, Sánchez-Castillo V, Clavijo-Gallego TA. Mapping the Landscape of Netnographic Research: A Bibliometric Study of Social Interactions and Digital Culture. Data and Metadata. 2023;2(25). https://doi.org/10.56294/dm202325

47. Diaków, D., Goforth, A. Supporting Muslim refugee youth during displacement: Implications for international school psychologists. School Psychology International. 2021;42:238-258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034320987280

48. Schnake-Mahl, A., Sommers, B., Sommers, B., Subramanian, S., Waters, M., Arcaya, M. Effects of gentrification on health status after Hurricane Katrina. Health & place. 2019;102237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102237

49. Iyanda, A., Lu, Y. Perceived Impact of Gentrification on Health and Well-Being: Exploring Social Capital and Coping Strategies in Gentrifying Neighborhoods. The Professional Geographer. 2021;73:713-724. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2021.1924806

50. Sanabria Martínez MJ. Construir nuevos espacios sostenibles respetando la diversidad cultural desde el nivel local. Región Científica. 2022;1(1):20222. https://doi.org/10.58763/rc20222

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Ariadna Gabriela Matos Matos.

Research: Ariadna Gabriela Matos Matos.

Methodology: Ariadna Gabriela Matos Matos.

Writing - original draft: Ariadna Gabriela Matos Matos.

Writing - revision and editing: Ariadna Gabriela Matos Matos Matos.